Acoustic Neuromas: What You Should Know

Overview

Acoustic neuromas, also known as vestibular schwannomas, constitute approximately six percent (6%) of all brain tumors. These tumors occur in all races of people and have a very slight predilection for women over men. In the United States, approximately ten (10) people per million, per year are diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma. This translates to roughly three thousand (3,000) newly diagnosed acoustic neuromas per year in the United States based upon a population of around three hundred million.

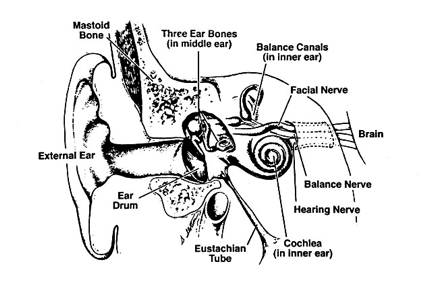

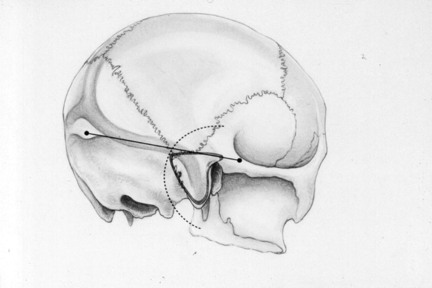

Figure A.

Illustration of the anatomy of the temporal bone and inner ear structures. The vestibulocochlear (VIIIth cranial nerve) nerve travels in a bony canal, the internal auditory canal, with the facial nerve. The brain stem and its vital structures are adjacent to this region.

Acoustic neuromas are benign fibrous growths that arise from the balance nerve, also called the eighth cranial nerve or vestibulocochlear nerve. (Figure A) These tumors are non-malignant, meaning that they do not spread or metastasize to other parts of the body. The location of these tumors is deep inside the skull, adjacent to vital brain centers in the brain stem. As the tumors enlarge, they involve surrounding structures which have to do with vital functions. In the majority of cases, these tumors grow slowly over a period of years. In other cases, the growth rate is more rapid and patients develop symptoms at a faster pace. Usually, the symptoms are mild and many patients are not diagnosed until some time after their tumor has developed. Many patients also exhibit no tumor growth over a number of years when followed by yearly MRI scans.

Acoustic neuromas occur in two forms: sporadic and those associated with Neurofibromatosis Type II (NF II). Approximately ninety-five percent (95%) of all acoustic neuromas are sporadic cases and are unilateral. In contrast, those tumors associated with NF II are bilateral and account for approximately five percent (5%) of acoustic neuroma patients. Patients with sporadic acoustic neuromas tend to begin having symptoms in middle age with the average being around fifty years old at diagnosis. Patients with NF II present at a younger age averaging around thirty years old when they first develop symptoms. There is a high degree of variability, however, and patients may begin having symptoms and be diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma during childhood or young adult life, as well when elderly.

NF II is a rare disease and is found in approximately one person per one hundred thousand population in the United States. In contrast, Neurofibromatosis Type I (a related, but different disease) is much more common being found in thirty to forty people per one hundred thousand population. Virtually every patient with NF II at some point manifests bilateral acoustic neuromas, while an acoustic neuroma in a patient with NF I is uncommon. Virtually no patients with NF I develop bilateral tumors as do those with NF II. Patients with NF II also have a propensity to develop benign nerve tumors in other locations which include other nerves that arise from the brain stem, as well as, nerves arising from the spinal cord and located more peripherally in the extremities. Patients with NF II, like all acoustic neuroma patients, benefit from the care of a team of experienced professionals who are capable of dealing with all aspects of their complicated case management.

Several treatment modalities are currently used for the treatment of acoustic neuromas. Until recently, surgical removal of the tumor was the standard form of therapy. Patients now also have the option of undergoing a noninvasive radiation treatment, called stereotactic radiosurgery (aka Novalis Shaped-Beam Surgery, Gamma Knife, Cyberknife, Protom Beam, etc.) to halt the growth of the tumor. Some patients might also be candidates for a combination of these therapies. The methods of treatment are discussed in detail below.

Treatment Options

The obvious goal of therapy of any benign brain tumor is to eradicate the tumor while preserving neurologic function. There are many factors which come to bear in terms of the success of treatment for these tumors. Acoustic neuromas, because of their location in proximity to delicate brain structures and cranial nerves, are a complicated treatment problem. The treatment of these tumors is best left in the hands of professionals who have a significant experience with their treatment. Experience in dealing with all aspects of treatment is important in order to maximize success and take advantage of all therapeutic options.

1. Surgical Therapy

Surgery for acoustic neuromas has been performed since the early 1900’s. The initial successes were few and far between by the early pioneering neurosurgeons who treated this problem. The past twenty years have witnessed an astounding improvement in our abilities to successfully deal with these tumors while preserving the neurological function of the patient.

In contemporary surgical treatment of these tumors, the vast majority of patients go on to lead a normal life following their surgery. The two main concerns that patients typically have is preservation of facial nerve function and of hearing. The facial nerve exits the brain stem and is anatomically in a position adjacent to the vestibulocochlear nerve. Preservation of facial nerve function is extremely important because of its cosmetic implications. Normal movement of the face on each side is controlled by the facial nerve. Any disruption leads to a loss of normal muscular tone and movement in that side of the face. Most experienced neurosurgeons treating acoustic neuromas report nearly 100% success with preserving the anatomical continuity of the facial nerve. Preserving anatomical continuity of the nerve means that the nerve is intact and was not disrupted by the surgical procedure. Even with an intact nerve, the functional abilities of the nerve may not be complete. However, results from most series over the years have shown excellent results in terms of functional outcome of the facial nerve.

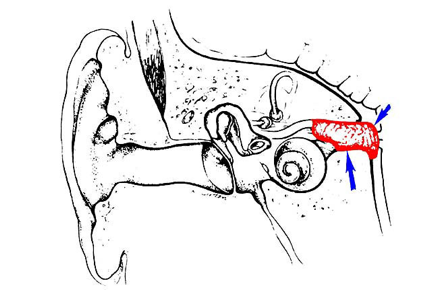

Figure B.

A small acoustic neuroma ( less than 1 centimeter in diameter) is typically confined to the internal auditory canal. As a tumor reaches medium size (between 1 and 3 centimeters in diameter) it extends out of the internal auditory canal and grows toward the brain stem.

One of the major recent focuses of acoustic neuroma surgery is the preservation of hearing. Major strides have been made in recent years in terms of improving the results of hearing preservation with surgery. Much like facial nerve results, the size of tumor is an influential factor. Also important is how well the patient hears prior to surgery. If the results of the hearing test (audiogram) indicate that the hearing level is sufficient to indicate a reasonable chance of success with saving the hearing during surgery, then a treatment approach is selected that is designed to save hearing. Otherwise, it may be advisable to choose a treatment approach that sacrifices hearing in order to obtain a total resection of the tumor.

Most patients with adequate pre-operative hearing levels have small tumors which are mostly confined to the internal auditory canal. In these cases, either a middle fossa approach or a retrosigmoid approach to the tumor is recommended. Continued refinements in this approach have led to superior hearing preservation results. In patients with small tumors operated by the middle fossa approach, good hearing has been preserved in roughly two thirds of those patients.

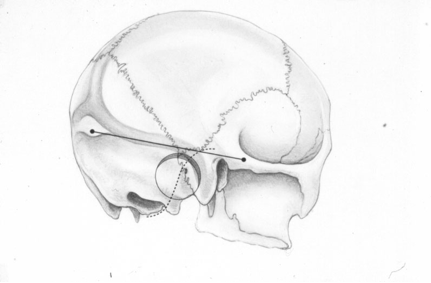

Figure C.

Large tumors are those which are at least 3 centimeters in diameter. These tumors press on the brain stem and cerebellum and involve other sensitive nerves which arise from the brain stem surface.

2. Surgical Approaches

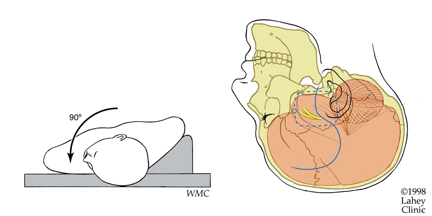

The choice of surgical approach depends upon the size of the tumor and the level of residual hearing detected on the audiogram. Again, the larger the tumor the lower the chance of saving hearing. The three most common surgical approaches for acoustic neuromas are the translabyrinthine, middle fossa and retrosigmoid approach. All of these procedures are performed under general anesthesia. Patients in general spend 5 days in the hospital, including the day of surgery. This however may vary widely amongst surgeons.

- Translabyrinthine Approach – The translabyrinthine approach involves an incision that is made behind the ear. The mastoid bone and the balance canal structures of the inner ear are removed in order to expose the tumor. This approach results in complete tumor removal in nearly every case. One of the main advantages in this approach is that there is little or no retraction of the brain required to provide excellent exposure of the tumor. Another advantage is early and direct localization of the facial nerve which facilitates separation of the nerve from tumor, optimizing facial nerve outcome. After completion of tumor removal, the opening in the mastoid bone is closed with a fat graft, which is taken from the abdomen, and reconstructed with bone cement to obtain a good cosmetic result.This approach sacrifices the hearing and balance mechanism of the inner ear. As a consequence, the ear is made permanently deaf. Although the balance mechanism is removed on the operated ear, the balance mechanism in the opposite ear provides stabilization for the patient. Sometimes patients experience transient vertigo immediately after surgery. This generally improves within the first five days following surgery and the patient has no further problems. In cases of larger tumors, the compensation for loss of the balance nerves on the tumor side has naturally occurred over time while the tumor has slowly grown to its large size. The patients rarely experience any vertigo in the early postoperative period.

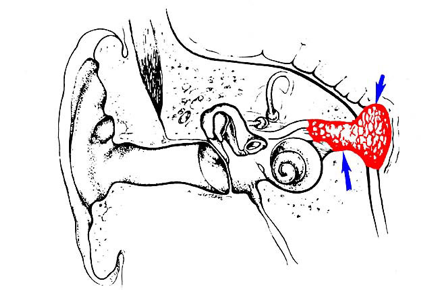

Figure D.

Figure D.

Outline of the incision (dashed line) and the area of bone removal on the skull by the translabyrinthine approach.Middle Fossa Approach – This approach is used for small tumors and is utilized in cases when hearing is to be conserved. An incision is made beginning just in front of the ear and extends upward in a curved fashion. A small opening in the bone is made above the ear, and the membrane that covers the brain is elevated away from the bone and gently held away from the bony floor of the skull. Bone is then removed over the top of the internal auditory canal to expose the tumor. Tumor removal is complete in the vast majority of cases. Every effort is made to preserve hearing and still completely remove the tumor. In these cases of small tumors, hearing is preserved in the majority of cases in our experience. Figure E:

Figure E:

Outline of the middle fossa approach incision and bone flap (dashed line) used for hearing preservation cases.Retrosigmoid Approach – An incision is made behind the ear and an opening in the skull is made behind the mastoid bone. The portion of the brain called the cerebellum is retracted away in order to expose the tumor. In most cases the tumor can be completely removed. Every effort is made in this approach to preserve hearing and still completely remove the acoustic neuroma. In some cases, because of invasion of the auditory nerve by the tumor, it is necessary to sacrifice hearing in order to completely remove the neuroma. The success of hearing preservation in these cases is largely dependent upon the size of the tumor and the condition of the auditory nerve in relation to the tumor.

Figure F.

Figure F.

Outline of incision and bone removal behind the ear for the retrosigmoid approach on the skull.3. Stereotactic Radiosurgery (“Novalis”, “Gamma Knife” Surgery)

Radiation therapy, in its various forms, has been applied to the treatment of acoustic neuromas. Historically this was done since the results of surgery in the past (prior to the 1970’s) were actually quite dismal in most cases. However, with improvements in microsurgical technique and surgical approach, as well as, the acquisition of great experience by some surgical teams, very few patients, until the past seven to ten years, have undergone any form of radiation therapy for their acoustic neuroma. However, stereotactic radiosurgery is utilized more and more for the treatment of these tumors. Though the goal of this therapy is tumor growth control, rather than removal of the tumor, complication rates are extremely low. The low chance of complications, and the outpatient nature of the technique, has led to its gaining wider popularity. In fact, it was estimated that in the year 2000, the number of patients treated with radiosurgery equaled the number of patients treated with microsurgery for acoustic neuroma in the United States. Furthermore, the number of patients choosing radiosurgery is greater than those choosing microsurgery since that time.

Stereotactic radiosurgery, or Novalis Shaped-Beam surgery, is a method of delivering a radiation dose in such a way as to minimize the affects of the radiation on the surrounding normal tissues while delivering a very high dose to the tumor. Low dose radiation beams are aimed from many different directions to converge on the tumor and, thereby, deliver a very high radiation dose. This type of treatment comes in several different forms. These methods are variously named the Gamma Knife, LINAC, proton beam therapy, and fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSR). The Novalis Shaped Beam system was chosen by the team at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio’s Cancer Therapy and Reseach Center (CTRC) for its versatility and precision in treating tumors such as vestibular schwannomas. Questions regarding the long-term results of this therapy have been answered in part by studies published in the past few years. These procedures are attractive to many patients because of the at least short-term promise of low complication rates and a shorter hospital stay. This form of treatment is an option for patients generally with tumors measuring less than 3cm in diameter. Few patients with larger tumors have been treated and therefore the efficacy of such has not been demonstrated to date.

Published series of patients treated by stereotactic radiosurgery have documented the various complications that can occur with this treatment. This includes facial paralysis, facial numbness, hearing loss, damage to the brain stem, hydrocephalus, and dizziness. The incidence of complications is extremely low in comparison to traditional surgery, however. Stereotactic Radiosurgery has become the generally accepted first line treatment for smaller tumors and has been shown to be quite effective at controlling further tumor growth. The question of long-term efficacy will not be answered for several more years when patients who have recently undergone this treatment are continually followed and studied for any recurrence of the tumor. Recent reports certainly have documented that it is effective in at least 90% of patients with tumors less than 3 cm in size and the durability of treatment appears encouraging.

Currently, patients of any age, or general medical condition may be considered candidates for radiosurgery. Certain factors will indicate that it is not the preferred form of therapy in an individual case. This is best discussed with a neurosurgeon who performs both radiosurgery and microsurgery for a balanced view of the risks of each form of treatment and the best chance of reaching treatment goals.

CASE STUDIES

Case 1

This 57 year-old woman presented with a several month history of tinnitus (ringing in the ears) in her left ear.. Her doctor sent her to an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist who ordered an MRI scan of her brain. A 2 cm mass was detected in the left internal auditory canal. (Figure 1) She was then referred for consultation to Dr. Day, who ordered an audiogram. Her hearing was intact at a near normal level on the audiogram in the left ear. After consultation it was decided that the best treatment in her case was total surgical removal of the tumor via a middle fossa approach to try and save her hearing.

Her tumor was totally removed. (Figure 2) The facial nerve function was perfect after surgery. Hearing was preserved within 10% of her preoperative level on audiogram. She spent 5 days in the hospital (including the day of surgery) and was back to work after a one month recovery period at her home. She has no residual problems after surgery and her tinnitus resolved by 3 months.

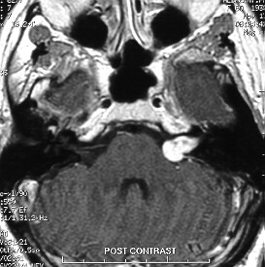

- Figure 1.

Preoperative MRI scan showing the 2 cm acoustic neuroma in the left internal auditory canal.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

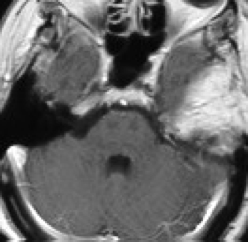

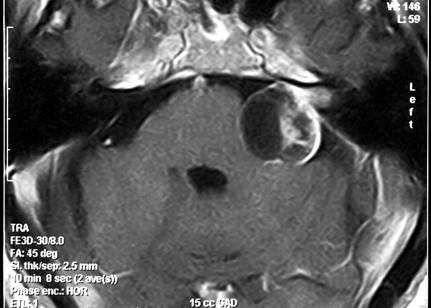

Postoperative MRI scan demonstrating total resection of the acoustic neuroma on the left. The whitish material on the left is a fat graft placed in the area of the surgery to seal off the space containing cerebrospinal fluid.Case 2A 70 year-old businessman noted several months of problems with balance and increasing numbness in the face. MRI scan was ordered by his personal physician. A quite large cystic mass in the cerebellopontine angle was discovered. This mass was pressing on the brainstem and the trigmeninal nerve, the nerve that provides sensation to the face. It was clearly the cause of the problem. After consulting with Dr. Day, the decision was made to perform a partial removal in order to ensure preservation of facial nerve function. Because of the age of the patient, this is an acceptable strategy in an older patient since the likelihood of recurrence in the patient’s lifetime is lower than for a younger patient. With such a conservative approach, if any tumor should regrow, this can be detected early and the patient can be treated then by stereotactic radiosurgery to minimize complications.

Figure 3.

Preoperative MRI scan showing a 3.5 cm cystic acoustic neuroma exerting pressure on the brain stem and cerebellum.

Figure 4.

Postoperative MRI demonstrating no visible tumor, though a thin (1mm) rim of tumor capsule was left against the facial nerve at surgery. With such a “radical subcapsular” removal, it is unusual for the patient to have regrowth of the tumor. The patient had no neurologic deficits as a consequence of surgery, made a full recovery, and actually improved neurologically with the pressure off of the brain stem and trigeminal nerve.Case 3

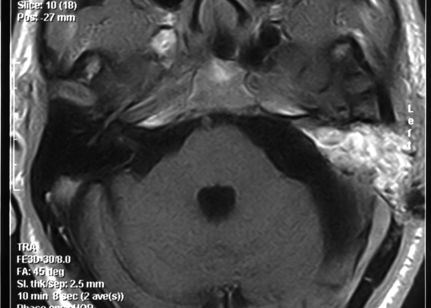

A 36 year-old woman noticed problems with her balance intermittently for six months prior to her referral. She had also been losing hearing in her right ear. An MRI scan revealed a large acoustic neuroma on the right side (Fig. 5). An audiogram demonstrated that she had totally lost her hearing on the right. After considering her options, she opted for translabyrinthine removal of the tumor.

The tumor was totally removed via surgery, with preservation of the facial nerve. Her facial nerve function was perfect and the patient returned to her previous job as a sales manager in one month.

Figure 5.

MRI of a large acoustic neuroma on the right in a 36 year-old woman.FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN THERAPY

Surgeons at the UT Health Science Center Center for Cranial Base Surgery are working to refine treatment strategies for patients with these tumors. Especially in the case of patients with very large tumors, a combined strategy of initial surgery to safely reduce the size of the tumor followed by Novalis Shaped-Beam surgery is ongoing and has thus far demonstrated superior facial nerve functional preservation results.

Scientists are working on various forms of treatment for acoustic neuromas that do not involve either surgery or stereotactic radiosurgery. The development of gene therapy may hold the most promise for a future cure of these tumors without surgery. Research is also ongoing in novel treatment strategies for other tumors that affect the base of the skull. Patients are involved in clinical trials of neuro-protective agents, which are being studied for their effectiveness at improving hearing preservation, as well as, facial nerve function after surgery for acoustic neuromas.

COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT ACOUSTIC NEUROMAS

- What is an acoustic neuroma? (vestibular schwannoma)

An acoustic neuroma is a benign growth which arises from the hearing and balance nerve that originates from the lower portion of the brain stem. These tumors represent approximately six percent (6%) of all brain tumors. - Is the tumor benign?

Yes. Acoustic neuromas are benign fibrous growths that are non-malignant, meaning that they do not spread or metastasize to other parts of the body. These tumors are, by nature, very slow growing in general. They affect adjacent nervous structures by creating pressure on these structures. - If I have one are my children at risk for developing an acoustic neuroma?

The majority of acoustic neuromas are unilateral and are not hereditary. Ninety-five percent (95%) of cases are sporadic and only involve one side. This is in contrast to those tumors which are associated with a hereditary disease called Neurofibromatosis Type II (NF II). In these patients, the acoustic neuromas are bilateral. This condition is hereditary. NF II is a rare disease and it is found in approximately one person per one hundred thousand population in the United States. If someone is diagnosed with NF II, they should undergo genetic counseling. - Why me? What causes these tumors to develop?

The exact cause of acoustic neuromas is not currently known. There is ongoing research at the House Ear Institute and other centers to try and determine the genetic defects that occur in the tumor cells. However, no specific environmental agents have been identified which causes the development of an acoustic neuroma. - Does my acoustic neuroma have to be treated?

The majority of patients who present with an acoustic neuroma do have treatment of the tumor. However, these are benign, very slow growing tumors in the vast majority of cases. Therefore, it should be understood that it is rarely an emergent situation to undergo treatment once this tumor is diagnosed. Patients have time to research their options for treatment and find an experienced team to manage their care. Those who do elect to be observed and not undergo surgery or radiation therapy for the tumor, in general, do not exhibit significant changes in the tumor over time as documented by frequent MRI scans. In a recently reviewed series of one hundred and nineteen (119) patients followed conservatively over a two and a half (2 ½) year average follow-up time, seventy percent (70%) of the patients did not exhibit any growth of their tumor. Those that do exhibit growth or cause symptoms may be treated either by surgical removal of the tumor or stereotactic radiosurgery. - Are there support organizations I can contact for information?

Yes. The “Acoustic Neuroma Association” is an excellent source of information. The organization provides educational material regarding acoustic neuromas and the various forms of treatment and can put you into contact with its local support group organizations. - What are the chances I will lose my hearing?

The chances of losing hearing prior to treatment depend upon many factors. Patients lose hearing due to these tumors from pressure effects of the tumor on the auditory nerve, as well as, invasion of the auditory nerve by the tumor. Similarly, the tumor can cause an obstruction of blood flow to the auditory nerve and the cochlea which results in hearing loss. Most patients present with hearing loss as the first symptom of their acoustic neuroma.The chances of losing hearing completely after surgery are dependent upon the size of the tumor and the level of hearing before treatment. Patients with poor hearing before treatment have a very low chance, with any therapy, of having their hearing preserved. Patients with better hearing have a much better chance of having their hearing preserved. As noted above, in a review of Dr. Day’s experience in more than 90 patients undergoing a middle fossa approach, roughly two thirds (2/3) of patients had their hearing preserved at a functional level.A recent publication examining a series of patients treated with stereotactic radiosurgery demonstrated that 60% of the patients reported at least some noticeable hearing loss by 4 years after radiosurgery. Therefore, a careful discussion with the treating neurosurgeon is necessary prior to making any decision concerning the form of therapy to be used. - What is the chance of losing facial nerve function?

An occasional patient presents with facial nerve weakness as the first symptom of their acoustic neuroma. These patients tend to be those with larger tumors. The risk of losing facial nerve function as a consequence of surgical treatment is dependent upon the expertise of the neurosurgeon and the size of the tumor. Patients with small tumors have an excellent chance of having excellent facial nerve function after surgery. Patients with small tumors can expect a ninety-five (95%) chance of excellent nerve function, as judged by our recent review of patients with small tumors treated by our team with a middle fossa approach. Only five percent (5%) had what is considered good facial nerve function. The chances of losing facial nerve function with stereotactic radiosurgery is very low at the current doses of radiation utilized. Recent data from patients undergoing current radiation doses show no more than a 2% chance of facial nerve weakness after treatment. - What is the chance the tumor will come back after treatment?

The chance of recurrence after surgical complete resection is extremely low. A study of over three thousand patients with acoustic neuromas who had removal of the tumor via a translabyrinthine approach demonstrated that the recurrence rate after total resection was 0.2% in these patients. Recurrence rates in other surgical series have, in general, been in the zero to two percent (0-2%) range after total resection. Recurrence after stereotactic radiosurgery is still undetermined at this point for patients with lower radiation doses, as are being utilized at the present time. The radiosurgical series “tumor control” rates over the short-term (i.e. approximately 2.5 years) are ninety-five percent (95%). A recent study of gamma knife patients showed that about 90% of patients had no further growth of tumor at 8 years after treatment. Most of those tumors in fact had decreased in size over that time. However, it is still unknown whether “tumor control” is equivalent to the low recurrence rates seen after total surgical resection (i.e. less than 1% chance of tumor recurrence). - What type of doctor should I be consulting about my acoustic neuroma?

Ideally, a neurosurgeon that has experience with the treatment of acoustic neuromas should be consulted. Many specialized teams exist at several centers around the country that have the necessary experience and frequently treat patients with acoustic neuromas. These are difficult problems that are best handled by an experienced, multidisciplinary team in order to provide the best chance for a good outcome. It is important to find out the level of experience of the physicians that are consulted. Patients should not be bashful in asking how many acoustic neuromas the doctor has treated within the past year, or in the past five to ten years, and what the results of that treatment were. Patients should expect to receive specific answers based on a review of the physician’s own personal data. It is important to find out the physician’s personal results with preservation of facial nerve function, hearing preservation, and the incidence of other major complications with either surgery or radiosurgery. Patients should probably be wary if a surgeon does not have easily produced statistical results (this usually means that he/she does not frequently treat these tumors). Likewise, patients should be wary of being treated by a physician who only occasionally treats this complicated problem. - Is this a tumor that any general neurosurgeon or otolaryngologist should be treating?

Again, the experience of the surgeon and sub-specialty training influences outcome to a tremendous degree. Patients should seek out an experienced neurosurgeon who frequently treats these tumors and can give sound advice based upon adequate experience.

- What is an acoustic neuroma? (vestibular schwannoma)

- Figure 1.