Section II: Current and Future Needs for the Care of those with Behavioral Health Needs in South Texas

Background to the Redesign of San Antonio State Hospital and Community Resources for Behavioral Health

1. Legislative History

In 2017, the 85th Texas Legislature recognized the need for improvements to the deteriorating conditions, outdated building designs, and inadequate information technology capabilities of the state hospital system. In response, the Legislature appropriated $300 million and authorized development of a master plan for each state hospital’s catchment area for neuropsychiatric healthcare delivery. This authorization followed several comprehensive reviews of the state of behavioral health services in Texas conducted by executive agencies and the Legislature. It also occured alongside other ongoing state and local government efforts to improve the processes, resources, and facilities for care.

The 85th Legislature directed that, where feasible, a public or private entity would lead development of the master plan. Accordingly, Texas Health and Human Services (HHS) contracted with the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHealth San Antonio) to develop in collaboration with stakeholders a planning guide for (a) facilities and clinical models to replace or enhance those currently at SASH, and (b) processes and care models in the community that can improve the outcomes of those with behavioral health disorders. The present document is the result of that undertaking.

2. Relevant Highlights of Select Prior Studies and Reports

Texas Legislative Budget Board Staff (2013): “Texas State Government Effectiveness and Efficiency Report. ID 187, Use alternative settings to reduce forensic cases in the state mental health hospital system”

This report (15) highlighted the tension between court rulings that admonish against holding individuals found incompetent to stand trial in jails for an unreasonable time and the limited capacity of the state mental health hospital system to meet current demand for services. Recommendations included (a) development and expansion of jail-based and outpatient competency restoration resources and other conditional-release dispositions, and (b) appropriation of funds to educate judges, prosecuting attorneys, and criminal defense attorneys on alternatives to inpatient treatment.

(i) CannonDesign (2014): “Analysis for the Ten-Year Plan for the Provision of Services to Persons Served by State Psychiatric Hospitals (SPHs)”

Authors (16) with architectural and engineering expertise conducted site visits to several state behavioral health facilities, including SASH. Their assessment of the infrastructure at SASH was blunt and dismal: “On average, across all three campuses, more than three quarters of all assessed buildings are either in poor or critical condition and only one in eight buildings was assessed to be in good condition.” Many hospital rooms lodge four or more individuals, exceeding accepted best practice of single or double rooms.

Based on 2014 utilization and service demand estimates, authors projected that SASH’s service region would need to add 56 beds for extended-stay hospital capacity.

At the same time, the continuum of care throughout Texas for those with severe behavioral health disorder had significant gaps. Moreover, integration between existing service providers at and between levels of care (inpatient and outpatient) was deemed inadequate.

Rural communities suffer from insufficient access to acute assessment and stabilization programming. This leads to increased burden on already-stressed emergency medical services and law enforcement when psychiatric crises culminate in behavioral disturbance needing intervention.

(ii) Department of State Health Services (2015), “State Hospital System Long-Term Plan”

Citing findings in the CannonDesign report, this plan (17) called for the renovation or rebuilding of facilities. It also proposed drawing a finer line between the tertiary care that state hospitals should provider, while striving to locate shorter-term assessments and acute care in individuals’ communities. Its recommendation to initiate or broaden contracting with local inpatient service providers, often through Local Mental Health Authorities (LMHAs), has been implemented.

(iii) Statewide Behavioral Health Coordinating Council (2016), “Texas Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan: Fiscal Years 2017-2021”

This (18) comprehensive assessment and action plan specified “urgent challenges and needs to both state-funded and state-operated inpatient psychiatric facilities by 2021” as a major goal. Facilities and maintenance upgrades and improved access were cited. Strengthening of the behavioral health workforce and improved coordination across resident-serving agencies were named among the long-term strategies with relevance to state hospital care.

(iv) Department of State Health Services (2016), “State Hospitals and Academic Partnerships”

This document outlined possibilities to involve the state’s academic medical centers into the operation of state behavioral health facilities. Such arrangements have been implemented at Texas Tech University Health Science Center at El Paso, and with UT Health Northeast in Tyler. Benefits that might result for patient care might include enhanced staff recruitment and retention, training and development of clinical staff in various disciplines, improved linkages with community services the academic center may operate, and access to leading-edge innovations. However, shortcomings in the hospitals’ current infrastructure and the exposure to financial risks for the medical schools were recognized as potential deterrents.

(v) Texas Health and Human Services (2017), “A Comprehensive Plan for State-Funded Inpatient Mental Health Services”

This report (19) proposed priorities and time lines for upgrading inpatient services statewide as earlier reports strongly advocated in three phases. Phase I’s proposal included the request for the preplanning phases preparatory to replacement of San Antonio State Hospital, which gave rise to the work of our group and this document. It also included requests for planning and design services and renovation of a vacant 40-bed unit to help alleviate current shortcomings in bed capacity. Construction of the replacement facility in San Antonio is a component of Phase II. Phase III, projected for the 2022-23 biennium, includes occupancy, implementation of evaluation processes, and the demolition, pending additional funds, of vacated, non- repurposable facilities.

(vi) House Select Committee on Mental Health (2016) “Interim Report to the 85th Texas Legislature”

The Committee’s assessment (20) of the state of behavioral health care in Texas covered the full continuum of concerns from prevention to caring for chronic illness. Hearings concerning the state’s own inpatient facilities included observations long-term plans to preserve their unique role have been hampered by infrastructure issues, increased demand for care, and reductions in bed availability. Facilities often did not operate at optimal capacity because of maintenance issues, outdated facilities, repairs mandated by regulatory and certifying agencies, and workforce recruitment and retention.

(vii) Center for Sustainable Development, UT Austin School of Architecture (2017): “A Texas Hospital: Planning Modern Psychiatric Care Facilities”

The Department of State Health Services (DSHS) engaged the authors to develop a model for new facilities on the site of Rusk State Hospital. The department had envisioned that this work could provide a reference point for other projects in the state psychiatric hospital system. This work aptly summarizes current data on the impact of design and the built environment on the well-being of people with severe behavioral health disorders, and current trends in the construction of such facilities.

The authors’ synopsis of best-practices in this area reflects innovations that, that have been influential in recent and ongoing projects in the U.S. and elsewhere. The leading themes emphasize structure and design that are more homelike than institutional, are safely accessorized and furnished to avoid the barren and sensory- deprived character of earlier settings, and endeavor to provide natural views and sunlight to the interiors. Easy access to the outdoors in pleasing but secure surroundings is also a prominent feature.

Patient rooms are predominantly single-occupant, with selective use of duplex rooms. Placing bathrooms en suite with each bedroom is also now widespread practice.

Common areas should contain subdivisions that allow congregation of both larger and more intimate groupings, as well as spots that provide individual calm space. The overall goal is to enable people to adjust the level of stimulation they experience to their current needs. Similarly, a recurring principle is to reduce perceptions of density and confinement. Some studies indicate that lessening the sense of compression caused by many people in a single limited space reduces aggressive behavior (1,21).

Estimated Trends in Behavioral Health Service Need

1. Population Growth

The Texas Demographic Center recent population projections for the San Antonio State Hospital’s service area (December 2018) indicate overall growth of 18% to occur between 2020 and 2030, from 6,493,188 to 7,664,279 civilian residents (22) .

Projections predict that those aged 65 and older will constitute a larger proportion of the service area population, increasing from 13.8% to 16.4%. Younger age groups will decline by a percentage point or so. The 45-54 year-old population is projected to rise from 27.15% to 28.4%.

The data also project that the proportion of those residing in Bexar County will change only nominally, from 32.24% to 32.65%. However, younger age groups (children, adolescents, and young adults) will become proportionately more concentrated in Bexar County.

2. Trends in High-Acuity Behavioral Health

Unfortunately, rates of psychiatric hospitalization and psychiatric emergency visits for children, adolescents, and young adults have continued to rise (10,23-25). These events are triggered most often in these age groups by mood and impulse control disorders. Among young adults, however, the largest increase in suicidal thoughts and behaviors is among those without a psychiatric disorder. This finding signals perhaps despair stemming from more adverse psychosocial circumstances rather than chronic psychopathology. On the other hand, psychiatric hospitalizations for the elderly declined considerably between 1997 and 2007.

Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorders have reportedly risen. In large part this trend reflects a less stringent threshold for diagnosing these conditions. This increase appears chiefly among youngsters with less severe impairments, most of whom also meet criteria for other disorders. Nevertheless, there are reasons to suspect that more severe forms of autism, such as those with comorbid intellectual disabilities or requiring significant assistance in daily functioning, will also increase. The suspicion stems from increases in those with risk factors for autism, such as the vastly improved survival rate for neonates experiencing neural insults, and the older age of fatherhood in the U.S.

There is no evidence that the conditions that are most prevalent among those in state hospital settings (schizophrenia, schizoaffective, and bipolar disorder that includes psychotic features or is treatment refractory) are becoming more common in the population.

Substance abuse among young people has been, fortunately, trending downward recently. In contrast to severe psychopathology whose prevalence in the U.S. is generally unrelated to geographic region, substance use does show regional variation. Texas is below the U.S. mean for most forms of substance abuse, though it is among the high-prevalence states for methamphetamine abuse and binge drinking (26, see state-level data).

3. Implications for State Hospital Inpatient Capacity

With a current population of approximately 6.4 million, a 300-bed inpatient facility represents 4.69 beds per 100,000. This is substantially below the national rate of 11.7 state hospital beds per 100,000 residents. Recent analyses (27,28) indicate that 20 per 100,000 is the minimum supply of this resource, bearing in mind that local variation in private inpatient services, utilization for forensic rather than strictly clinical objectives, and community-based resources can influence the impact of public hospital inpatient capacity on fulfilling actual need. The current wait list and length of time to admit referred patients (see Appendix B) amply show the latent need that current capacity leaves unmet.

The CannonDesign report from 2014 recommended that SASH add 50 beds to meet its projected needs. That proposal assumed that Rio Grande would take on portions of the SASH catchment area, but it has only 55 adult beds. On the other hand, the Casa Amistad 16-bed facility in Laredo, which functions administratively as part of SASH and was included in its bed count, is set to shift to operation by a local agency. A replacement facility for SASH that maintained the current nominal number of beds would gain 16 or so on campus.

It is unlikely that replacing SASH and slightly expanding its census in San Antonio would translate into an oversupply in the foreseeable future. It appears to be below the bed supply in comparable states. Nevertheless, expansion of a single facility beyond 300-350 patients pushes the limits of its ability to meet the objectives of current design principles and management resources. As population growths spurs increases in service demands, a more appropriate expansion of inpatient capacity would probably involve developing additional facilities to the south and west of San Antonio, which would also be closer to the home counties of many patients currently coming to SASH.

Optimal use of the bed supply in a rebuilt SASH will require more efficient use of the time patients spend in the hospital in order to reduce time to discharge and minimize readmissions. It also means reversing the tide of hospitalizations purely for trial competency goals that lack compelling clinical need for hospitalization. This report endeavors to provide a foundation for hospital-specific and system-wide innovations to achieve these objectives.

Stakeholder Concerns & Challenges for the Region’s Behavioral Healthcare System

1. Access to Care and Inpatient Capacity

a. Overall Shortage of Behavioral Health Inpatient Beds and Brief Lengths of Stay

Reflecting the diminishing supply of inpatient services for behavioral health, the limited availability of bed for individuals who need extended treatment in a state hospital is among stakeholders’ leading concerns. LMHAs that operate short-term stabilization facilities or have access to local inpatient facilities through private- purchased beds (PPB) contracts experience frustration that many individuals who seem unsafe for discharge lack appropriate postdischarge alternatives. “Our biggest challenge is discharging patients regardless of stability since [ours] is not a long-term facility, rather a short-term crisis stabilization facility”, said one program director at an LMHA. Public safety officials express similar concerns with respect to the short lengths of stay prevalent in community settings. “When we send a patient to a community hospital, they are only there for 2-4 days and we are constantly having to pick them up again and bring them somewhere,” said one officer. A community psychiatrist observed, “I work with patients that need long term stabilization. When the patient is chronically ill, they require longer stays than a free-standing psychiatric hospital can offer. SASH should serve this population.”

Law enforcement agencies, especially in rural areas, encounter similar difficulties with those who come into their custody for behavioral disturbances and have clear treatment needs. One law enforcement official said, “There are patients that we are uncomfortable with releasing, because they are a danger to themselves and to others.” The problem of appropriate discharge options for behavioral health patients who come to local hospital emergency departments is a persistent demand on staff resources. Emergency rooms report waits of 36-72 hours for a suitable behavioral health bed. Law enforcement personnel often need to locate an appropriate facility and provide transport for them. Bexar County has improved this process through an integrated system implemented by the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council (STRACC) that shows dispatchers in real time where available beds are located, but rural areas with fewer overall facilities remain encumbered with these frequent situations.

HHS currently provides local LMHAs with funding to contract with inpatient facilities to enable access for patients who need hospital level care, especially those without health care funding. Referred to as PPBs (private-purchase beds), some of these contracts involve acquisition of a specified number of beds for LHMAs to fill as need required, while others pay for each bed-use day. The latter has a greater risk that there is no bed available to the LMHA. Stakeholders report that this is an extremely valuable resource, “a game changer” as one put it. They also have the significant advantage of proximity to a person’s home community. But community providers recognize that their role is chiefly a temporizing one, and it does not fulfill the same care functions that longer-stay hospitals perform. They are unsuited programmatically (oriented around short lengths-of-stay), and their physical characteristics are generally not conducive to extended stays. One recent report from an HHS advisory group indicated that readmission rates are lower for patients discharged from a state hospital than from a contracted bed, reflecting greater challenges in maintaining close communication and coordination with private psychiatric hospitals.

In our meetings with family members and patients, some lamented that inpatient treatment resources for early illness were not more like SASH. Instead, the frequent short-stay hospitalizations they experience seldom allow for adequate cross- titration of medications to determine a regimen’s effectiveness. The pressure imposed by insurance and other payers to “do something” often leads to starting new medications. The practical effect is an accumulation of medications used simultaneously whose individual benefits are unclear, but whose adverse effect risks are well established.

The net result is that LMHAs care for many individuals with treatment needs that exceed that emergency departments and local acute-care psychiatric settings can provide. This exacerbates demand for beds at SASH. This gives rise to concerns about the long wait time for SASH admission, and broad uncertainty about how admissions to SASH are prioritized, as discussed next.

b. Desire to Standardize Admission, Discharge Processes and Wait List

Throughout the SASH catchment area, there is near-unanimous frustration among stakeholders regarding the lack of predictable access to SASH. Many noted that the lack of standardized processes has led to barriers in care. Reports of inconsistencies in admission criteria were related in all local stakeholder sessions. For example, it was reported in some areas that admission had been denied to people who reported any substance use, while other areas stated that they have never had an issue placing someone who reported substance use. Similarly, there is also a need for clarity around placing clients at SASH who have a co-occurring intellectual or development disorder and a serious mental illness, with key informants reporting that those admissions are determined on a case-by-case basis.

Relatedly, the wait list data available to community providers is an ongoing source of confusion. Local Mental Health Authorities (LMHAs) are responsible for adding individuals to a list of civil patients for whom SASH admission is requested. HHS central office maintains the Clinical Management for Behavioral Health Services (CMBHS) wait for SASH, which LMHA’s update when a person in their catchment area is requesting admission. Concurrently, SASH itself has an informal internal list that can be highly discrepant from the CMBHS list. This list includes additional referral sources beside LMHAs, such as clinicians, clients, and agency and law enforcement officials. Nevertheless, the CMBHS’s is the outward-facing “official” list that LMHAs consult. On a given day, the CMBHS list may have 10 or fewer people, while SASH itself has 30-40 potential admissions pending.

Discrepancies between the two lists have led to the troubling perception that admission to SASH is an unpredictable process. That perception in turn spurs clinicians and families to forgo the formal admission process and instead work through informal channels. This further contributes to the number of referrals not reflected in the CMBHS data. As a result, enormous of effort of SASH’s clinical staff goes toward screening phone calls from clinicians, clients and officials seeking an admission for a client.

Another problem is that LMHA staff find the CMBHS system itself unwieldy and difficult to enter patients needing inpatient care, which makes its use error-prone and inaccurate. This problem has been recognized, and SASH has provided education, and referrals to their local contact person for further support. Despite these efforts, the follow up is very poor, and this results in few individuals being added to the list and numbers are discrepant with other rosters maintained in Austin.

Stakeholders throughout the catchment area expressed concern that what constitutes “medical clearance” appeared unpredictable over time. Stakeholders find it difficult to prepare people for SASH admissions without knowing exactly what will be accepted and declined, how best to advocate for patients, and what case information is necessary for admission.

In addition to individuals with comorbid substance abuse or IDD, other patient groups that posed significant placement problems for local providers included pregnant patients and adolescents. These populations require special consideration in the current redesign effort and future development of the campus since they are most at risk of experiencing adverse outcomes because of lack of services.

c. Acute-Care Patients Admitted to SASH

On top of the role that state hospitals play for individuals who require inpatient care that exceeds the programmatic and length of stay limitations of other settings, SASH also admits patients for acute care that ideally other hospital settings provide. This obviously hampers the state hospital’s ability to fulfill its more unique function in the system of care, which should be meeting the needs of patients who have had prior hospitalizations with insufficient benefit. Scenarios leading to SASH admission for those preferably served in local short-stay acute inpatient settings often involve rural counties that have no beds available and unfunded patients needing hospitalization but the LMHA’s private-purchase bed allotment cannot be applied or is depleted. Various reports by state agencies recommended phasing out state hospitals’ use in this context, but the lack of alternatives continues to compel it. Hospitalization of youth at SASH in clinical circumstances that would ordinarily warrant other inpatient services closer to home is a major concern discussed below.

Another route by which patients not in demonstrable need of longer hospitalization are admitted have included those where SASH is fulfilling a mandate under the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), despite SASH’s more specialized services. Relatedly, individuals often present to SASH by themselves for evaluation; sometimes families literally drop a patient with serious mental illness off at the front gate. In these situations, urgent clinical need may warrant admission even though other inpatient providers would be more suitable.

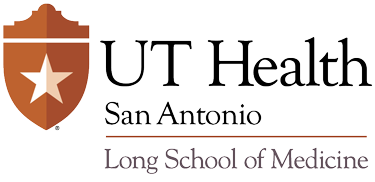

Table 1 contains length-of-stay (LOS) information for adult patients discharged during fiscal years 2012 and 2017. These data do not differentiate between those in civil and forensic commitments.

Table 1 contains length-of-stay (LOS) information for adult patients discharged during fiscal years 2012 and 2017. These data do not differentiate between those in civil and forensic commitments.

Three notable trends are:

- The number of discharges dropped dramatically over this period, coinciding with a substantial longer average length of Increased forensic commitments are a known contributor to these trends. Start shortages that compelled restrictions in admissions at various times during this period were also contributory.

- At least one-fourth of patients had hospitalizations shorter than 10 It would appear this represents at least in part those admitted to SASH for acute intervention because there were no other acute-care facilities available.

- Length of stay increases with This is consistent with some aspects of severe mental illness over time. They are often progressive conditions, so chronicity begets greater impairment. The pattern fits the “downward drift” finding that as individuals age their familial support network dwindles, which, in tandem with worsening illness, increases the likelihood of poverty and medical indigence, and thus fewer discharge options.

d. Individuals Frequently Using Inpatient or Emergency Facilities for Behavioral Health Support

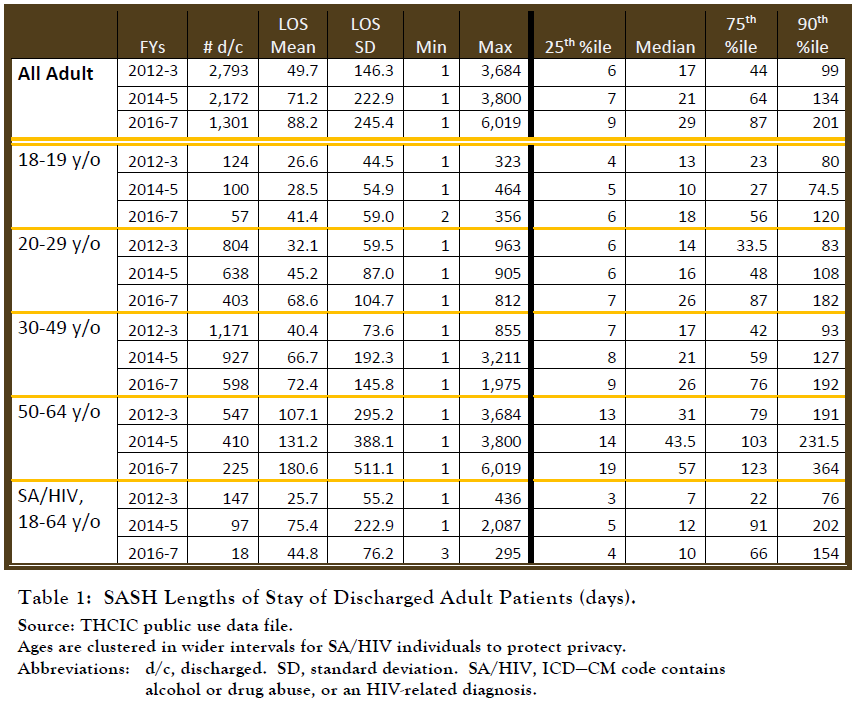

In 2017 Capital Health Care Planning, in conjunction with Methodist Health Ministries and the Meadows Health Policy Institute undertook a study of “Super utilizers”, defined as persons in the “Safety Net Population” who had either 1) three inpatient hospitals, 2) two inpatient hospital stays and a serious mental illness diagnosis or 3) more than nine (9) emergency room visits. They identified 3,717 individuals. Features of this population include:

- One of five were homeless

- Annual Emergency Department visits ranged from 0 to

- Annual inpatient admissions ranged from 0 to 23

- 50% had a serious mental illness

- 20% had an indication of a substance abuse problem

- Most had one or more chronic medical

The Capital Planning study broke down the diagnoses (both mental health and non-mental health) and looked at the costs to the health care system of the failure to stabilize these patients. Table 2 shows these costs which total over $136 million a year.

Difficulties in helping these individuals maintain functioning to avert the events that precipitate emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalization would improve access for limited inpatient resources and reduce the high costs to the system that ensue from serial crises.

Difficulties in helping these individuals maintain functioning to avert the events that precipitate emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalization would improve access for limited inpatient resources and reduce the high costs to the system that ensue from serial crises.

e. Lack of a Crisis System

Several LMHA leaders stated their system of care lacks necessary crisis alternatives for people experiencing a mental health crisis. While inpatient bed options may exist, the wait time for admissions is lengthy. Psychiatric crisis options include extended observation units, crisis respite, or 23-hour observation units. However, these types of options are not available in many of SASH’s rural counties, which leaves the burden of care on general emergency departments at community hospitals. This situation is often exacerbated when an emergency detention warrant is not in place or expires, and emergency departments must discharge a person before a transfer option is in place to move that person to an inpatient psychiatric facility. In several focus groups, organization leaders voiced the need for more acute care options, stating they currently only have pre- and post-crisis treatment services available. LMHA staff noted that they have no contract options for clients who need detoxification services, which is another alternative that has potential to alleviate back up and wait times in the crisis care system.

In one focus group, LMHA administrators indicated that due to a lack of crisis respite services in their area they must send clients for crisis respite in other areas. This particular rural LMHA sends those clients to a neighboring LMHA for adult crisis respite, but the cost for these services drains their already limited resources. The LMHAs touched on the need for crisis respite services, especially since many clients do not meet YES Waiver program or intellectual and development disability qualifications for community respite. These stakeholders indicated there is not enough crisis respite for families in their community, and that they are often left to refer people to an emergency shelter instead. While LMHAs may contract with respite services in other areas, LMHA leadership estimated that 90% of their clients decline these services because of the lengthy travel required to access it.

f. Limitations on Satisfactory Options for Post-Discharge Care

Behavioral health services need a range of intervention and support models that straddle the traditional inpatient vs. outpatient office visit dichotomy. However, implementing and sustaining programs that do so has proved difficult not only in South Texas but across the country.

Our region has a range of outstanding delivery models that serve the goals of maintaining individuals within their communities and supporting their functioning. Examples include day treatment programs, respite centers for youth, assertive community treatment, wraparound services for youth, and other interventions. Crisis stabilization units, operated by LMHAs or other entities, have been beneficial in preventing many flare ups from culminating in hospitalization. However, essentially none are universally available, and some instances service need increases caseloads beyond what is considered appropriate for these supports to be optimally effective.

Community providers in the SASH catchment area spoke about many unique and innovative programs that help local communities fill gaps in services. The most commonly mentioned innovative programs included efficient triage and referral services, crisis beds, and opportunities to contract with hospitals outside of their facilities. These initiatives help reduce boarding people with psychiatric issues in emergency rooms. Other programs help to reduce front-end crisis wait times, like the Law Enforcement Navigation System in Bexar County. People needing emergency services are triaged by MEDCOM, a dispatch center that accepts calls 24 hours a day, seven days a week for trauma clients in the region, and psychiatric facility referral calls.

Nevertheless, many individuals with severe illness have few community options. Hospital-level care or other high-supervision variants (ESUs, CSUs) seems necessary for the foreseeable future.

One patient seen recently at University Hospital epitomizes the predicament of individuals for whom appropriate community placements are lacking.

JD is a 45 year-old man with mild intellectual disability and schizophrenia. He received special education services until age 21. He had numerous psychiatric hospitalizations beginning in childhood, due to severe behavioral disturbances, including aggression. When he was 24, JD had the onset of unremitting hallucinations and paranoia. He began antipsychotic medications while a psychiatric inpatient at University Hospital. He resided with his mother whose worsening renal disease left her unable to provide supervision of treatment adherence and structure; mother died when JD was 30. He frequently stopped taking his medication and would respond to command auditory hallucinations. Neighbors would find him wandering the street. He rang doorbells and demand food, and his interactions were increasingly belligerent and for which police were called. After mother’s death, he briefly lived with his sister.

Ultimately JD was taken into the custody of adult protective services, but few group homes would accept him. Persistent aggression and disorganization made his time in a group home precarious. Police were called following an incident of genital exposure to a female staff member followed by attempted physical contact of a sexual nature. He was hospitalized at UH where, despite resumption of medication, he required 1:1 supervision for poor interpersonal boundaries, lack of independent ADL skills, and severe behavioral outbursts that followed the slightest frustration. When asked how he was feeling, he responded, “Pumpkin pie is very good”.

While waiting for an opening at SASH, his behavior became somewhat more settled and adapted to routine, and a community group home offered him a trial stay. Upon arrival, conflicts with began almost immediately. He became agitated over something, and he exited the back door of the group home. He wandered down the street and banged his leg against a piece of sharp, exposed concrete on a neighbor’s use. EMS was called and transported him to a local emergency department so that his leg could be sutured. He then waited for 36 hours for a new psychiatric bed to become available. The cycle would begin again.

2. Care Coordination, Communication with Local Providers

a. Community Views on Care Coordination

Community providers and public safety agencies also expressed a range of views concerning discharge planning. “When we send a patient to SASH, they will stay for 90 or so days and we won’t get a call about them afterwards,” said one law enforcement official. Others were appreciative of SASH discharge planners’ collaboration, especially LMHAs whose staff make regular visits to maintain contact with patients they have hospitalized there.

Stakeholders also reported significant variation in the discharge process. While providers in some regions reported that they participated in discharge planning and had been given notification prior to patient release, some law enforcement stakeholders reported they had little to no notice and “lost” people when they left the SASH campus. According to one sheriff’s office representative, “[SASH] would call and say that we need to pick them up right away, or they will release them, even if the patient has a court order. They ended up releasing [patients] on the streets and we [have] to go and find them. They need to give rural counties time to [plan] and travel there.” In addition to the variability in the notification of client release, stakeholders shared that discharge paperwork, which includes medication, treatment, and related information, is often unavailable and can take well past 14 days from discharge to receive. This has led to a lapse or change in treatment by the community provider of origin, which could be avoided with a proper discharge protocol. Families mirrored this sentiment and reported that they did not receive any sort of aftercare planning or coordination. Several family members of SASH clients reported that they located resources on their own, and often shared that their loved one had relapsed back into their illness because of lack of connection to treatment.

In addition to stakeholders repeatedly reporting a lack of collaboration with SASH staff for discharge and aftercare planning, several catchment area stakeholders expressed concern about the unavailability of information about the treatment plan itself. Families of former patients mirrored this concern, noting that they had difficulty accessing and communicating with SASH treatment team staff regarding the patient’s care. While key informants routinely characterized treatment at SASH as excellent, community providers and family members indicated that it was more difficult to share information about the patient’s treatment and behavior history with SASH staff once the patient had been admitted. In interviews with family members, many people reported how carefully they keep histories of their loved ones (including information about medications, doctors, and treatments) that could be helpful in expediting decisions about medications while the client is at SASH.

Community providers also reported a strong desire to continue support and communication with their patients during their treatment with SASH for better continuity and transition of care, regardless of whether community providers collaborated directly with SASH staff. When community providers are able to maintain communication with their clients during the clients’ stay at SASH, they are better able to engage and encourage clients’ progress beyond discharge from SASH.

b. Appropriate Information at Admission

At the same time, inpatient clinicians feel stymied the lack of important treatment-relevant data when patients arrive. Among things of utmost importance is an up-to-date record of pharmacotherapies, current and past. For instance, patients are admitted and if they have received treatment with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic preparation, there’s no information on when it was last administered nor, often, at what dose. This obviously complicates getting symptom-relieving treatment under way.

The majority of those coming into state hospital care have illness that has proved treatment-refractory to date. Very few, certainly of the adult patients, are treatment-naïve. That makes treatment history essential to guide interventions in the hospital. If a person had treatment with a medication at an adequate trial and duration and experienced either no benefit or adverse effects, then it is at best pointless, and at worse life-threatening to use it again simply because today’s prescriber didn’t have enough details about it. On the other hand, records may indicate that a certain regimen was prescribed and discontinued, but with insufficient information about dose, duration, and outcomes it is hard to know whether re- initiation of the compound might be useful.

3. Rising Forensic Utilization Constrains Service Availability Based on Clinical Need

Another major driver of reduced inpatient capacity is the increased use of the state hospital for court-ordered evaluation and treatment following determination that an individual is incompetent to stand trial (IST). In Fiscal Year 2018, 27.4% of state hospital admissions in Texas admissions were transferred directly from a jail or correctional facility, preponderantly for IST commitments. Cited often by local stakeholders as a throttle on SASH availability for individuals who need longer term hospital care, it is also a growing concern nationwide (29). However, Texas’ proportion of state hospital beds used for this purpose has shown among the largest growth relative to other states (9). Our percent of forensic admissions relative to total state hospital admissions was 45% in 2014, while the national median was 18%. The problem is well-known to Texas state government. Among other reports on the topic, in 2013 the Legislative Budget Board recommended developing alternatives to state hospital beds, such as expansion of outpatient competency restoration programs, especially for misdemeanor defendant (15).

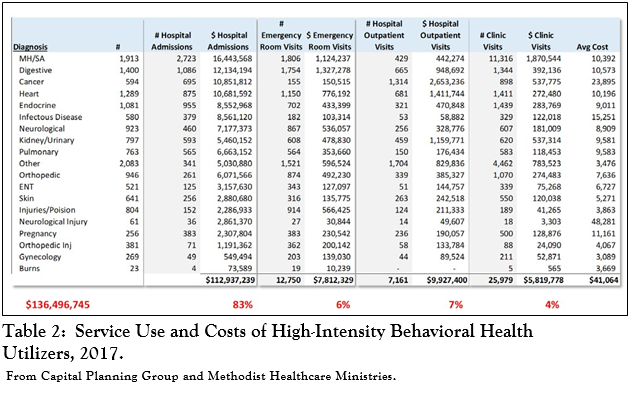

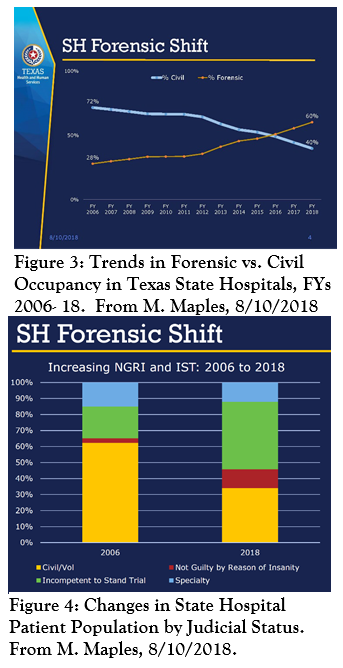

The trend toward a larger proportion of publicly-funded inpatient capacity for hospitalizations related to the judicative competence of those facing criminal proceedings has continued in the state. Mike Maples, the Deputy Executive Commissioner for Health and Specialty Care, shared data presented to the Judicial Council on Mental Health, which indicated that patients in the state hospital system on forensic remands surpassed those admitted under civil procedures in FY2016. The former now constitute 60% of the population (Figure 3).  Within the forensic population, those hospitalized due to adjudicative incompetence now represent the largest segment cared for in the state hospital system (Figure 4). In growth terms, the largest proportional increase is in occupancy by those found not guilty by reason of insanity, although few of these individuals are at SASH. Average length of stay for the forensic patient population is far greater than for civil patients, 170 vs. 71 days.

Within the forensic population, those hospitalized due to adjudicative incompetence now represent the largest segment cared for in the state hospital system (Figure 4). In growth terms, the largest proportional increase is in occupancy by those found not guilty by reason of insanity, although few of these individuals are at SASH. Average length of stay for the forensic patient population is far greater than for civil patients, 170 vs. 71 days.

This development was spurred by Federal rulings that detainees with behavioral health disorders should be placed in treatment settings rather than jails. Nevertheless, the wait for defendants in Texas to transfer from jail custody to a state hospital bed averaged 296 days.

The current situation manages to combine the systemic disadvantages of constricting state hospital beds for those with clinical need for this unique service and persistence of the problem greater hospital use sought to solve.

Local mental health care providers blame the diversion of SASH resources toward forensic roles, especially IST, for the difficulties they encounter with admitting patients to SASH. “Eventually the state hospital will be all forensic”, was a lament heard more than once. These agencies receive mixed messages about discretion in allocating beds between civil and forensic patients at SASH. One LMHA representative expressed concern that the designation of beds for forensic commitments contributes to the lack of available beds for civil commitment patients at SASH, even when these beds are not in use. This executive was told that unused forensic beds could be used for civil commitment purposes, but he has yet to see these beds used for civil commitments. The majority of stakeholders we interviewed were adamant that beds for civil commitments should be protected at all costs, and civil beds that have been transferred for forensic use should revert back to their original use for the region.

In Texas, the initial remand of a defendant to an inpatient psychiatric facility for competency restoration lasts 60 days for misdemeanor charges and 120 days for felonies, after which a single 60-day extension may be granted. Where studied, approximately 70% to 80% of those referred for competency restoration inpatient services attain competency. Differences between localities in their thresholds for IST determinations, latencies to begin treatment, and treatments themselves hinder generalizations, but it seems that most defendants who attain competence do so within 1-2 months, with the likelihood of competence diminishing with longer periods; within a 6-month period, about 80% of defendants attain adjudicative competence (30-32).

The factors correlated with attainment of competence are the chronicity and initial assessment of severity of psychotic symptoms, initial assessment of judicial knowledge, and age (30-34). Younger individuals who may not have had prior treatment or have been sufficiently adherent with treatment for psychotic illness are more likely to experience greater improvements with adequate care. Those who have been ill for longer and perhaps more refractory to pharmacotherapy have a less favorable course. This will not surprise psychiatric practitioners, for whom the prediction of who is ‘restorable’ within, say, six months or even less is not difficult when history and current deficits are accounted for.

Nevertheless, it is not uncommon for individuals who will not attain competence to be held on IST commitments for much longer periods based on judicial direction to care providers to, essentially, ‘keep trying’. Concerns about public safety influence these determinations, especially for individuals who would not fulfill criteria for civil commitments based on the usual criteria of dangerousness to oneself or others. For instance, an individual who has shown problematic behavior in his home community (disorderly conduct, assaults, domestic violence), may receive an extension of IST commitment to keep him or her from posing risks when civil commitment criteria would not apply. The Supreme Court’s 1972 Jackson ruling found that essentially open-ended involuntary commitments based on IST violate the Constitution’s due process provisions. However, it is widely known that state compliance is poor, both in statute and in practice, partly due to ambiguities in the ruling itself, especially the vagueness of a “reasonable period of time” for IST-related confinement (35).

It is also no secret that in many communities and judicial districts hospital commitment of an individual found IST is a well-intentioned maneuver to get proper care for him or her. Well-meaning defense attorneys may pursue this course to obtain treatment for their clients, even when the charges at issue would not ordinarily result in incarceration. Defendants/patients may not regain competency but treatment may have improved the patient’s condition to the point they are no longer dangerous to self or others, and thus not civilly committable.

There are also significant consequences for the state’s county jails when IST patients cannot be discharged from state hospitals. Patients with more severe illness in jails also cannot be transferred to SASH for treatment.

4. Episodes of Behavioral Disturbance in the Community Place High Demand on Law Enforcement Resources

After families and health care professionals, police officers are perhaps those most involved with individuals suffering from acute behavioral disturbances that arise from psychiatric illness. It is underappreciated by the community how much police work is devoted to successfully managing situations in which an agitated or desperate person with grossly impaired judgment poses a risk to self or others. Only a fraction of these incidents culminates in chargeable offenses. Far more often officers assume the difficult work of defusing a situation and frequently transporting an individual for appropriate behavioral health or medical care. The legal mechanism for holding and transferring a person in this context is issuance of an emergency detention order or, less often, a mental health warrant by a judge or magistrate.

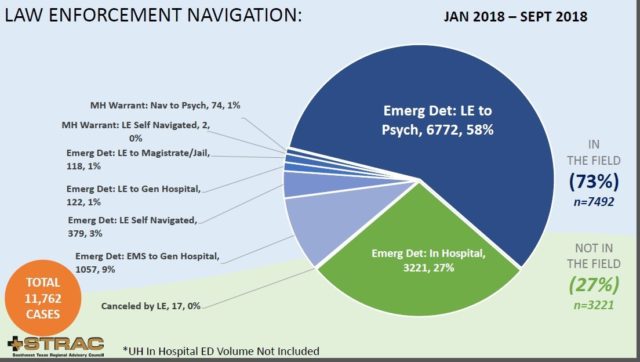

Bexar County recently implemented a regional system to expedite efficient dispatch and triage of emergency calls to appropriate facilities. Operated by the STRAC and developed by its Crisis Collaborative program, its innovations include real- time information about which facilities are suited to the individual’s safety and treatment needs and can accept him or her. Besides the immense operational benefits the system yields, it also furnishes vital data on law enforcement’s engagement with those in behavioral crises. Information on the services to which individuals are ‘navigated’ provides a particularly visit picture or community need and law enforcement activity in this area.

From January 2018 through September 2018, STRAC’s navigation system captured 11,762 episodes of law enforcement involvement owing to behavioral health disturbances (Figure 5). Averaged over time, this represents 43 per day in Bexar County alone.

A significant number of calls (27%) were from hospital emergency departments requesting police officers to obtain an emergency detention order to effect transfer to a specialty psychiatric facility. Combining these incidents with the 6,846 that culminated on transfer to psychiatric facility “from the field” yields a total of 10,067 episodes resulted in an individual brought for care to a behavioral health facility. The latter include crisis stabilization and extended observation services operated by the Center for Health Care Services as well as hospital-based psychiatric services. Of course, these data exclude emergency situations that lead to inpatient or similar admission but do not involve calls law enforcement.

Although the law enforcement navigation system has made triaging mental health crises more efficient, the number of incidents is still alarming. More detailed clinical information from these encounters is expected when the TAVHealth system comes online, but it is common knowledge that most of the individuals who required law enforcement involvement to address a behavioral crisis have extensive treatment histories, compelling the inference that gaps or ineffectiveness of community care and other supports may have been inadequate.

The implications for law enforcement outside of Bexar County are even more severe. Given fewer resources and options nearby, time and travel to locate an accepting facility and complete the transfer involves an enormous devotion of law enforcement effort.

5. Large Service Region: Long Travel Times and Diverse Local Care Resources

Even by Texas standards, the area served by San Antonio State Hospital is immense.

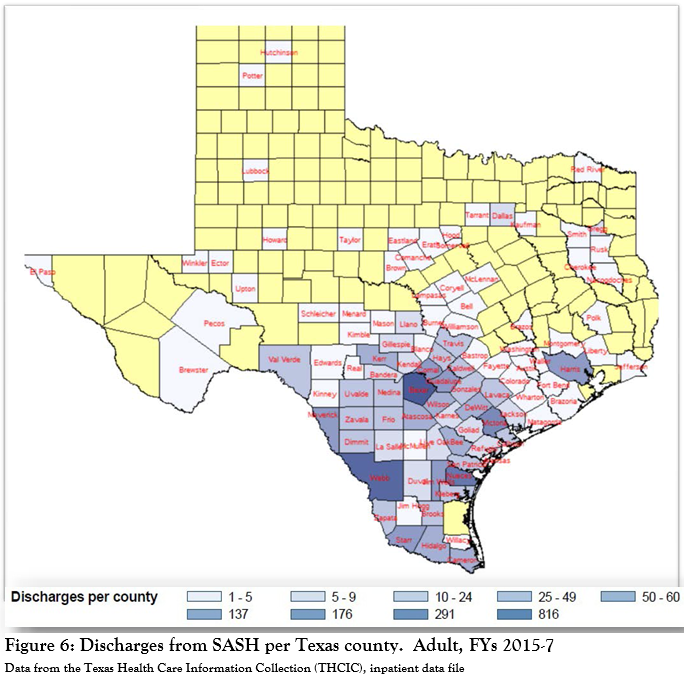

Figure 6 shows the number of adult patients discharged in fiscal years 2015- 2017 coming from individual counties in Texas. It is not the case that SASH’s patients are predominantly from the San Antonio area with the numbers of patients falling off as a function of distance. In fact, only 31.7% of adult patients come from Bexar County, as do 44.3% of adolescents. A substantial number (11% of adults, 5.3% of adolescents) come from Webb County, but it is unclear how many adults were treated at the Casa Amistad site in Laredo or at the main SASH campus.

Figure 6 shows the number of adult patients discharged in fiscal years 2015- 2017 coming from individual counties in Texas. It is not the case that SASH’s patients are predominantly from the San Antonio area with the numbers of patients falling off as a function of distance. In fact, only 31.7% of adult patients come from Bexar County, as do 44.3% of adolescents. A substantial number (11% of adults, 5.3% of adolescents) come from Webb County, but it is unclear how many adults were treated at the Casa Amistad site in Laredo or at the main SASH campus.

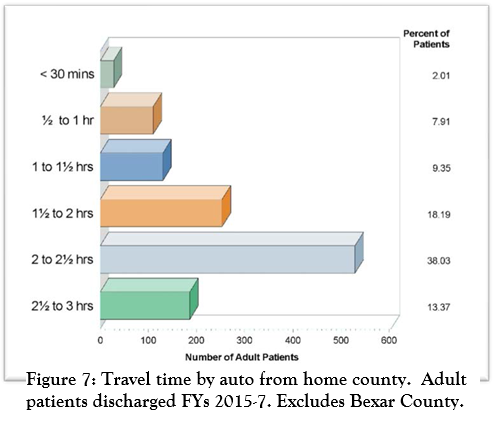

Figure 7 shows estimated travel times by automobile under ideal conditions from patient’s home counties other than Bexar; computations used the county seat and SASH main address as origin and destination points. Over half (51.4%) of adult patients from outside Bexar County, or about a third of all SASH patients, come from communities with a minimum one-way auto travel time over 2 hours. Assuming patients’ main social and familial supports reside in the same area, clearly being so far removed is isolating for them and complicates effective transitional programming.

Figure 7 shows estimated travel times by automobile under ideal conditions from patient’s home counties other than Bexar; computations used the county seat and SASH main address as origin and destination points. Over half (51.4%) of adult patients from outside Bexar County, or about a third of all SASH patients, come from communities with a minimum one-way auto travel time over 2 hours. Assuming patients’ main social and familial supports reside in the same area, clearly being so far removed is isolating for them and complicates effective transitional programming.

There is, moreover, a significant burden on families to maintain contact with their hospitalized kin, because many of these households do not have extensive resources to afford lost work time, travel expenses, etc. The presence of family housing on campus to reduce the drain of one-day roundtrip travel is an important asset that stakeholders felt should be expanded.

Distance also makes it problematic that SASH serves as the resource for acute care for many patients from rural areas. When transport is the responsibility of law enforcement, there is the added consideration that resources are diverted from other public safety duties. Many key informants, particularly those in counties located a great distance from SASH, agreed that alternative treatment options for adults are also needed to meet acute care needs and provide extended observation and screening to identify appropriate referrals to the state hospital. At the SASH retreat, many participants voiced support for a regional approach to developing these capacities.

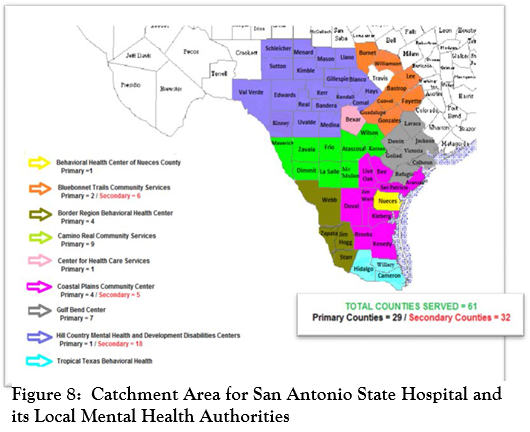

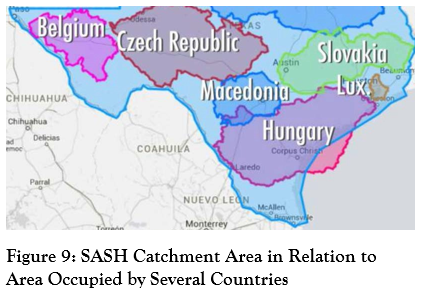

One corollary of the high geographic dispersion of patients’ home counties is the number of local mental health authorities (LMHAs) with which the state hospital needs to coordinate (see Figure 8).  The map shows SASH serves several culturally and geographically diverse areas, from the urban areas of San Antonio and Corpus Christi to the growing areas of the Rio Grande Valley, as well as large swaths of the Hill County and West Texas. To illustrate how vast this region is, Figure 9 shows that several European countries could fit into the SASH catchment area.

The map shows SASH serves several culturally and geographically diverse areas, from the urban areas of San Antonio and Corpus Christi to the growing areas of the Rio Grande Valley, as well as large swaths of the Hill County and West Texas. To illustrate how vast this region is, Figure 9 shows that several European countries could fit into the SASH catchment area.

Note that for the larger urban counties such as Nueces and Bexar SASH is “primary”, indicating that both adult and adolescent patients are served by SASH. “Secondary” counties are parts of LMHA’s for which only adolescent patients are served by SASH. For example, in Hill Country Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Centers has only one primary county (Comal) that sends adult patients to SASH, while the all the other 18 counties are secondary, meaning that their adolescent patients are served by SASH. This Ieads to considerable confusion among the public and mental health providers to which counties are served and by whom. One patient in Comal County may be sent to SASH, while another just over the county line in Kendall County will be sent to Big Spring State Hospital in Wichita Falls.

6. Rural Areas Need Inpatient Capacity Beyond EOUs and CSUs

The state provides funding to Local Mental Health Authorities (LMHAs) for a patchwork of other programs including Extended Observation Units (EOUs) which are 8-16 bed small units that can serve persons admitted under a Warrant for Emergency Detention for up to 48 hours, five Crisis Stabilization Units (CSUs) of 8-16 beds that may serve persons under Warrants for Emergency Detention or Orders for Protective Custody for up to 14 days, and a variety of contracts for the purchase and use of inpatient beds in private psychiatric hospitals. These programs are intentionally designed and funded to provide short-term, acute psychiatric stabilization services and not long-term psychiatric treatment.

EOU, CSU, and private psychiatric beds are consistent with the state plan and are extremely necessary and appropriate for persons who require only a few days of intensive treatment. These services allow for the person’s condition to stabilize to the point where that individual may safely return to the community and continue with his/her recovery in outpatient treatment. They exemplify cross-agency coordination, and state/local and public/private partnerships along with access to services. They are not designed or funded to provide treatment for persons whose psychiatric deterioration is so severe that they require inpatient services beyond a fourteen-day period. Moreover, private psychiatric beds are the most expensive forms of treatment in the inpatient continuum in terms of their costs per bed day, the private hospitals are located only in urban areas, and they are not designed nor do they desire to serve persons with extremely serious psychiatric disorders who require longer term treatment.

The problem remains that once an individual has reached a maximum length of stay in an EOU, CSU, or private psychiatric hospital, that person still must be transferred to a facility that has the capability of serving people on 45-day civil commitment orders. These facilities do not have adequate numbers of beds to serve a state of over 28 million people, and in most cases are hours away from the communities in which the individuals in crisis are located. For example, the nearest psychiatric facilities, either state- funded or private, are a three-hour drive in any direction from Del Rio and nearly as far from Eagle Pass. Likewise, the state hospital is a three plus hour drive from the Rio Grande Valley and more than two hours from Victoria even on those rare occasions when a bed at the hospital is available. This is extremely traumatic for a person in psychiatric crisis who must endure the transport while handcuffed in the back seat of a law enforcement vehicle. It also causes hardship to an already overburdened law enforcement system that must remove personnel from their regular duties to provide the transport, resulting in a shortage of manpower available for routine law enforcement functions and often extremely high overtime costs. It is counter-therapeutic as the individuals often are indigent and their families cannot afford the time or costs to travel those distances to visit and participate in their loved one’s treatment.

Another negative impact is that EOUs, CSUs, and private facilities either are forced to hold persons beyond the time for which they are legally authorized because to release them would endanger the individuals or they are forced to release them, and if needed, re-apprehend and recommit them which causes additional and unnecessary trauma to already psychiatrically compromised individuals. It also places short-term facilities in direct competition with hospital emergency rooms and law enforcement environments for already scarce or unavailable beds in the existing state- operated or funded system.

7. Impediments to Recovery and Community Tenure after Discharge: Insufficient Housing, Healthcare, and Treatment Continuity

Stakeholders uniformly expressed grave concerns about difficulties the chronically ill individuals whom SASH treats in obtaining stable housing, healthcare, and behavioral health treatment continuity after discharge. Community providers remarked that there is a lack of benefits upon discharge, which makes it hard for patients to obtain necessary follow-up services.

At least 16% of adults admitted to SASH during FY 2018 from settings other than correctional/jail facilities were homeless. It is unknown how many of those transferred from jails were homeless prior to their arrests. It is uncertain how many individuals discharged from SASH become homeless or in unstable residential situations (e.g., bouncing between relatives, shelters, and others for brief periods), but state hospitals do frequently discharge patients to homeless shelters. Federal data indicate that point prevalence of the total homeless population varies year to year, but while the overall trend between 2010 and 2015 for Texas overall showed a marked decline of 32.6%, Bexar County experienced a reduction of only 12% (36). If, as 2016 estimates indicate, half of the state’s residents with SMI, SPMI, and SED are medically indigent (no property, not someone’s dependent, unable to reimburse care, and below 150% of Federal) poverty level, that would be the lower bound of medical indigence among state hospital inpatients, a strong correlate of homelessness. Precarious living arrangements are obviously not conducive to a treatment regimen over an extended period, and homelessness is both hazardous and likely to sustain psychiatric disability. Few would include homelessness and the social isolation it often entails as compatible with recovery. There was strong interest and support for transitional housing to help re-establish an individual’s skills at negotiating community life, and for more permanent housing solutions.

Sustaining medical treatments is also a growing concern, especially for the large cohort of discharged patients without insurance. We heard of successful integrated primary care projects, in which internal medicine practitioners treated patients in behavioral health settings but were discontinued due to reduced funding or due to changes in 1115 waiver projects. Even when patients received medical attention, problems filling prescriptions were frequent. Changes in pharmacy benefits between inpatient and outpatient care led to instances where the latter’s formulary did not include medications patients had received in the hospital.

Uneven availability of behavioral health and supportive services after discharge remains a generic feature of health care throughout the country, especially when urban and rural areas are compared. However, in our region stakeholders from even relatively resource-rich portions perceive large gaps. Some reflect the difficulties obtaining or maintaining adequately staffed specialized services. Others reflect discontinuities created by weak communication and planning with the state hospital. “We need a strong ACT team when a patient transitions to the community after discharge; there are no consistencies or protocols put in place for transition services at the state hospital when they discharge a patient”, was how one provider put it. Inpatient services should “create an environment of recovery and resiliency as a person transitions into the community; we need coordination and continuity of care for these patients”.

8. Infrastructure and Location

Nearly all the previous studies and reports (noted on “Relevant Highlights of Select Prior Studies and Reports”) recognized the dire situation of SASH’s physical infrastructure, with particular concern about patient care areas. The inpatient units themselves have completed their useful lives, and their replacement is timely if not overdue. Setting aside their current condition, even the basic layout of these units does not comport with what has been best-practice for some time now (37). Forty-bed units are relics, and not conducive to comfort and engagement by patients. Single- person bedrooms are preferred, and double rooms the guideline- concordant maximum for adults. En suite bathrooms that contain at least a toilet and sink are preferred and should be accessible from bedrooms without requiring corridor entry unless extenuating circumstances compel otherwise. The minimum standard is one bathtub or shower for every six occupants who do not have a bathing facility at their bedroom. The number and areas of consultation, conference, group activity and social spaces are often below specifications for a service with 40 patients. Stakeholders also found the layouts not conducive to easy staff-patient interactions, which perhaps contributes to some patients becoming agitated to gain attention.

“The space now for adult’s visitation is just one big room with the TV on. The staff members are watching television, which makes it hard to talk without distractions. The environment is not conducive to having good communication with the patients – we need less noise. We aren’t allowed in residential areas, so we are stuck with the room that has loud TVs, couches and some tables.” – Family member

Besides these core deficiencies, stakeholders and other visitors find the general ambience on patient units as exceedingly institutional and unappealing. Experiences with the destructive behaviors of a few patients on furnishings has contributed to an even more barren and austere environment. The building housing the adolescent unit is from another era entirely and its lack of sound-absorbent furnishings led one visitor to liken it to an “acoustic torture chamber”.

Visiting currently takes place in a central area to which patients are escorted. This has some advantages for supervision and safety compared with on-unit visiting but is also out of step with family and patient centeredness and the contemporary practice of nursing staff providing informal, individually tailored psychoeducation and functional support strategies to families. It is therefore common to have a number of comfortable visiting facilities adjacent to an inpatient unit to facilitate interaction with both loved ones and with the staff caring for the patient.

Food is delivered by service trucks from a central facility that chiefly reheats the partially pre-cooked meals vendors provide. Delivery time to patients on the units is likely to exceed the thermal insulation capabilities of the trays so hot meals do not arrive at the appropriate temperature. Today’s preferred practice is overwhelmingly to provide fresh food when possible. Proper nutrition for those with behavioral health disorders is virtually life-extending due to their susceptibility to cardiometabolic dysfunction (38).

“As we begin to look at safety as the only thing, we are missing the point of treatment. We started with privacy curtains, but that became dangerous. A patient is in a room with three other people who are also going through mental illnesses. Our doorknobs were taken off and we started to lose our sense of being a human. There are people restrained, which I think is a power control to keep people safe. We constantly heard “code green.” There are times where you feel stripped of humanity and your belongings could get stolen, which made you feel on edge. It is hard to feel safe with all these environmental factors” — Recent SASH patient

Stakeholders also observed that the lack of modern information technology infrastructure hampered staff use of wireless devices now routinely used to, among other things, track point-of-service events like medication administration, vitals, and so forth.

A major asset of the SASH campus is its open landscape and varied topography with hills that afford pleasing natural views.

Its location in San Antonio is currently distant from other health care providers and potential vocational or rehabilitation settings that would ordinarily be accessible to individuals in the process of transitioning to community living. The planning group is very interested in making transitional living services available to SASH’s discharged patients, and the current site is an appealing location, notwithstanding distance to other resources that would promote community involvement.

9. Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disorders

Community providers expressed concern that patients, both youth and adult, with developmental disorders cannot access inpatient behavioral health care:

- “We are seeing more kids that are diagnosed with autism and aren’t getting admitted into SASH. We need more opportunities for extended care.”

- “One of the criteria for admission is that our patients cannot have an IQ below 70, but that is our whole population. There is nothing here to provide services and they need 1:1. When hospitals hear about IDD, they don’t admit the patients.”

- “It is almost impossible to get autistic adolescents into a hospital, especially when they are aggressive or a danger to their parents and themselves.”

- “There are some respite centers, but they do not admit patients who are aggressive.”

- “We are told to go to a respite center or a state school.”

- “SASH needs services for co-morbidities with IDD individuals. Insurances won’t cover nonverbal patients because they can’t successfully complete mental health treatments a respite center or a state school”.

This is not a new problem nor one unique to SASH, although it remains a complex one in the context of inpatient services.

We recognize this as an area of unmet need, one that can be addressed satisfactorily only in the context of the range of local day program capacities, specialized behavioral support services that help community caregivers to promote adaptive behaviors, and clear expectations for the indications for psychiatric inpatient care.

10. Children and Adolescents

a. Proper Role for SASH in Continuum of Care for Youth

Even more than for adults, state hospital services for youth are ordinarily for those who, despite previous inpatient stays and other community-based educational, family, and mental health services, require a secure setting for an extended period to ameliorate severe symptoms. Acute-care, short LOS facilities seldom have the infrastructure for appropriate education and activities, including out-of-door recreation needed for youth in 24-hour care settings for long periods. On the other hand, they are usually more abundant and geographically distributed, which makes them better suited for family involvement and school liaison which are fundamental elements of child and adolescent psychiatric care.

Accordingly, state hospital inpatient services are to be used sparingly for youth with demonstrable need. Above all, SASH is distant and burdensome for many families, who often have other children and limited resources to support travel. However, the limited availability of secure services for youth experiencing behavioral health crises has led to SASH serving as the main acute inpatient resource for many adolescents, especially those residing in rural areas.

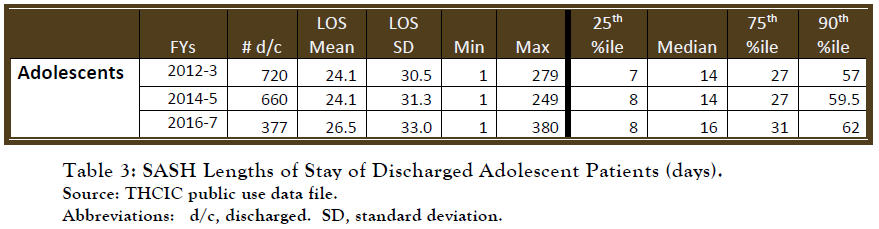

Lengths of stay data reflect the high reliance on SASH for short-stay clinical care, concurrent with a substantial cohort who have longer-term hospitalizations. For patients discharged in FY2016-7 combined, the average stay was 26.45 days. However, 50% were discharged in less than 17 days, which is the median LOS. At the same time, 25% were in hospital for more than 31 days, and 10% more than 62.

b. Distance and Family Separations are Burdens that May be Counterproductive for Treatment

If short-stay episodes are highly beneficial and associated with low readmission (e.g., <15% over six months would be impressive for this patient group) then perhaps current utilization is justifiable. Provider stakeholders are concerned about the shortage of psychiatric beds for youth, and concentrating them at SASH, which should serve those with longer-term care requirements, is probably not the most effective way of satisfying community need. Providers in some locales experienced a significant reduction in number of beds available from adolescents while need for them has risen. “One of the hardest things for children is the separation of families. It would be ideal to keep the children closer to home”. “Parent cooperation is very important during treatment. When families hear they have to travel far, families are not as interested.” Consequently, many stakeholders questioned the appropriateness of treating children and youth at a state hospital at all.

A single site located far from communities imposes burdens and possible adverse impacts on care. Law enforcement or LMHA personnel often devote full days to transporting youngsters to and from SASH: “We have to have some of our employees transport the patient and often have to also pick them up because the parents can’t go.” “Because of our financial situation, we have to worry about transportation and maintenance costs to transport our children.”

Separation of families at the time of hospital admission, only for logistics and resources and no compelling safety concerns, is worrisome. Law enforcement officials, who often arrange transportation from rural areas to state hospitals, are troubled by the experience for youth and families: police car transport for a child or youth, coupled with an active mental health crisis while leaving family behind can be traumatic and worsen rather than improve the child or youth’s mental health. No doubt there are situations in which youth have no adult on hand to accompany them to the hospital. This salone testifies to the immense care needs of children who have experienced unsuccessful surrogate-care placements. Admitting these youth to an inpatient setting without family or at least a familiar social service worker present to provide essential information for clinical assessment, not to mention to minimize the sense of abandonment, is atypical of good child psychiatric practice. The adolescent clinical staff at SASH is talented and committed; they should have the benefit of these individuals on hand for clinical decision making. Only rarely, in our experience, are written records alone of adequate quality for this purpose.

The majority of stakeholders expressed a preference for alternative options within the child and youth’s community in lieu of a stay at SASH or any state hospital. Several key informants noted that the majority of children and youth have access to health care benefits for behavioral health inpatient services; therefore, payment for services becomes less of a concern should alternative community treatment options be developed.

c. Day Treatment and Educational Services

There are lifelong adverse implications when youngsters lack resources and opportunities for academic skills development commensurate with their abilities. Many young people with behavioral health conditions also have difficulties at school, which can be a direct complication of their behavioral/emotional disturbances, often compounded by a comorbid learning disorder (39). Many hospitalized youth need specialized educational and psychiatric services in an integrated day program, for at least a brief period to help them experience success, academically and socially, in age- appropriate milieus including school. For some, it may be the only path to graduation. There are a few such day treatment of partial hospitalization programs in Bexar County, including at Clarity Child Guidance Center. However, attendance is limited by the requirement that parents provide transportation back and forth. In many other localities in the country, the local school district is to provide this service for students attending special programs for mental health reasons. Recouping tuition costs from the home district can also be cumbersome and affects the sustainability of these services.

11. Substance Abuse Worsens the Outlook for those with Behavioral Health Disorders

Substance abuse (SA) disorders are practically endemic to many severe psychiatric illnesses. Persistent drug and alcohol abuse are known to worsen prognosis for these conditions. Unfortunately, for those at high risk for the development of psychiatric disorders, substance use may hasten their onset, essentially cutting short the period to consolidate good premorbid functioning, which is an important predictor of functional outcome. The direct neurotoxic effects of many drugs of abuse may in some instances be etiological factors, the pathophysiology of which may result in disturbances less treatable with current medications. Of course, substance abuse also has its own heightened risk for early mortality.

At University Hospital, 80% of patients admitted to the inpatient psychiatric service test positive for either illegal drugs or alcohol on admission. Among patients who are admitted to the medical-surgical services and who also have a psychiatric condition, rate of positive drug/alcohol screen is 50%.

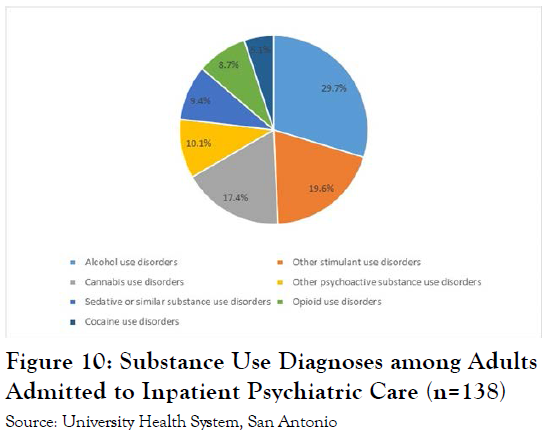

An analysis was done of patients admitted to the University Hospital psychiatric inpatient unit over the period July 1 to September 30 of 2018. As shown in Figure 10, of the 247 admissions to the service, 138 (56%) were formally diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Not everyone who tests positive for a drug on admission receives a full diagnosis of substance abuse, but often the use of substances exacerbates the underlying mental health condition.

An analysis was done of patients admitted to the University Hospital psychiatric inpatient unit over the period July 1 to September 30 of 2018. As shown in Figure 10, of the 247 admissions to the service, 138 (56%) were formally diagnosed with a substance use disorder. Not everyone who tests positive for a drug on admission receives a full diagnosis of substance abuse, but often the use of substances exacerbates the underlying mental health condition.

Stakeholders were consistently alarmed about the challenges and service gaps in treating patients with comorbid SA disorders. Many community psychiatrists have a policy of not treating individuals with SA. Some LMHAs have detoxification and sobering units that fill a major service need and offer a singular opportunity to engage individuals in treatment to alter their pattern of use.

Overall, there was strong endorsement by provider and family stakeholder of the need for those hospitalized at SASH and elsewhere to have interventions that target substance abuse.

12. Caring for Patients with Medical Needs

Stakeholders also raised concerns about what type of primary medical care is available at the state hospital for pregnant females and geriatric patients. It was stated throughout the interview process that people with co-morbid medical needs are often turned away because of a lack of physical health care at SASH. If a need arises for urgent medical treatment during a person’s stay at SASH, he or she must be moved to a neighboring general acute care hospital for services. Many stakeholders from across the catchment area expressed the opinion that, at minimum, the state hospital should be able to treat urgent medical treatment needs and certain chronic illness such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

Stakeholders affiliated with emergency service agencies also advocated that the replacement facility have infrastructure flexibility and capacities to care for injured patients and house staff in the event of natural disaster that hinders movement to other locations. Preparedness for power outages was also recommended.

13. Behavioral Health Workforce, San Antonio State Hospital

Stakeholders and the public at large are keenly aware of the precarious workforce situation at SASH. Periodic unit closures and suspension of new admission over the years because of staff shortages and widely known in the community. In most open-ended discussions about SASH within this region, the topic comes up early. Curtailments in service, including recent unit closures, due to staff shortages were perplexing and upsetting for many community providers. “There is a staffing issue for SASH – the reduction of staffing is counter-intuitive to the level of acuity in patients they serve,” said one. In addition, frequent departures of colleagues can be demoralizing to the staff that remain.