Section III: Redesign of Facilities for San Antonio State Hospital

Facility Redesign I: Clinical Practice Models and Processes for Optimal Care During and After Hospitalization

1. Refocus SASH’s Service and Admission Patterns to Serve as a Tertiary Treatment Center

We strongly endorse the recommendations from numerous prior evaluations that Texas’ state-operated psychiatric hospitals become almost exclusively “tertiary care facilities for the most complex mental health patients and a significant portion of the forensic population” (16,17,19).

2. Regional Cooperation to Standardize Admission Criteria and Readiness for Transfer

It is important to address the perception that SASH’s and LMHAs’ admitting, discharge, and follow-up processes waitlist are inconsistent, inadequately informative, or just inscrutable to one another. We propose organization of a regional council comprising LMHAs, SASH, and other relevant groups charged with improving communication concerning, among other things, admission criteria, timely exchange or accurate clinical data at admission and discharge, availability of appropriate post-discharge services, coordinating follow-up care, and so forth.

“Whatever we build, there needs to be an adequate number of beds for the territory you are responsible for. SASH is not insurance driven, so the treatment and discharge plan can be fulfilled. There are staffing issues due to wages, but discharge and treatment plans should be standardized.” – Family member of SASH patient

3. Beyond ‘Beds and Meds’: Promote Recovery and Readiness to Resume Community Life

a. Functional Assessments and Preparation for Community Reintegration

Besides being a worthwhile goal in itself, helping patients to attain the skills for living in nonhospital settings is essential to the behavioral health service system. There is no desire to keep increasing inpatient psychiatric capacity; this means that the 300 or so state hospital beds planned for this growing region must keep lengths of stay as short as possible and the time patients spend as productive as possible.

For individuals with longstanding impairments, symptomatic relief does not spontaneously lead to recovery of functions that were at their peak perhaps years earlier, if indeed they were ever attained. And, naturally, time in hospital only contributes to their atrophy. A robust rehabilitation program is not a luxury nor just a humane gesture to help people spend their time enjoyably – it is now central to the mission of state hospitals that aspire to discharge patients in better shape than when they entered. Length of hospitalization may contribute to establishing an effective medical regimen for symptom reduction. The countervailing force is the functional debility that accompanies long term disuse of daily living skills.

Direct assessments of functional status and needs will be vital if SASH beds are to turnover to meet community needs. Even if an appropriate range of outside support services develop, they vary in the degree of independence expected on users. Determining optimal settings for a given person using evidence-based methods to evaluate level of functioning is a critical need for SASH to perform. Over- restrictiveness contradicts the state’s proclaimed objectives of fostering independence and recovery. Exposing patients to new environments without adequate preparation is also unwise, with potential for disastrous consequences (40).

The new facility’s infrastructure and appropriate staffing should therefore have robust rehabilitation capacities. These need to be in the areas of personal care/hygiene, management of unstructured time (cultivation of affordable and enjoyable pastimes), financial management, independent travel, the logistics of making and keeping appointments, medication adherence, nutrition, social engagement, and spiritual development.

The current vocational services offered include a half-day program for selected patients, and on unit experience in some work-related tasks. Home skills and cooking groups are offered weekly at most. It is unclear whether the latter provides adequate assessment and rehabilitative opportunities, and new infrastructure must support an appropriate availability and frequency to serve both purposes.

Adequate staffing and transportation must be available to enable off-grounds trips and activities. There will always be risk inherent in every undertaking, and we all do our best to avert bad outcomes. However, it is alarming when the institutional response to an unauthorized departure by a patient during an outing, or even a series of them, leads to the curtailment of such important experiences for everyone.

Our consultations with the rehabilitation team left no doubt of their commitment, competence, and ingenuity. They are huge asset because the interpersonal aspects of cultivating and sustaining motivation for healthy lifestyle changes are perhaps the most important. The replacement facility affords an exceptional opportunity to overcome the limitations in space, access, and physical capabilities that have hampered engaging patients and the optimal frequency and range of activities.

b. Trauma-Informed Care

The experience or threat of extreme or chronic harm, especially interpersonal violence, or witnessing horrific incidents of this nature, is a risk factor for behavioral health disorders. Growing appreciation of this relationship has led to a related principle, that recovery for many individuals must include interventions that take account of traumatic experience, as well as resource to alleviate post-traumatic stress disorders per se.

Many aspects of such trauma-informed care include processes that most would agree should be part of treatment for everyone. For instance, SAMHSA guidance on trauma-informed care includes six principles: safety, trust and transparency, peer support, collaboration and mutuality, promoting autonomy (empowerment, voice, and choice), and appreciation of an individual’s context (cultural, historical and gender issues).

Trauma-informed care also involves tailoring treatment that takes due account of one’s traumatic experiences and the unique risks that some exposures hold. For instance, a youth removed from a home where maltreatment included having been locked in a closet may suffer terribly when forcible seclusion is used for out-of-control dangerous behavior; other avenues may be more appropriate. Situations associated with physical vulnerability, such as disrobing, bathing, toileting, and physical examinations, may also be avoided by traumatized individuals. Therefore, reluctance to shower or use the bathroom may not just be symptoms of psychiatric illness but can be addressed in a manner that gradually affords greater comfort in doing them in an environment of safety and privacy. Those exposed to emotionally abusive environments may have strong aversive reactions to criticism – that does not mean a person should just be pacified and get no corrective feedback, but that what some may tolerate is inordinately distressing to others.

We encourage staff education and training in these issues and that such staff development be continuous to stay current as this area advances.

c. Peer Support Specialists

A robust peer support program helps make positive adjustment outside the hospital a more tangible reality for patients when those who have navigated this journey provide information, support, and encouragement. We encourage SASH to integrate peer support programs and ensure their quality through training, patient and family feedback, and due appreciation of the roles peers play. The latter might include assistance with travel, a formal recognition program, educational opportunities and other benefits for those making this important contribution.

d. Physical Fitness and Health

Age-adjusted death rates among individuals with behavioral health disorders are consistently found to be higher than general population rates, with the worldwide estimate of increased mortality risk of 2.2 (38). Using data from 1997-1999, those served by public mental health services in Texas had a standardized mortality ratio relative to other Texans of 4.6. Comparable estimates for other states were lower except for Oklahoma.

Fitness has a connotation of recreation, and therefore, by association, an optional activity one can just as soon take or leave. However, their elevated risk for all-cause mortality makes physical fitness critical for those with behavioral health disorders. Benefits of exercise on mood are strong and effects on cognition are also becoming recognized. Providing resources, support, and incentive to follow physical activity guidelines is more similar in importance to moving a medical inpatient to avert bedsores than to an optional way to pass the time for those who are interested.

Infrastructure that enables staff to provide and monitor fitness activities includes a mixture of resources close at hand to inpatient units (for guided moderate exercise, outdoor walking and other activities), and some centrally located facilities (such as for more extensive strength training and specialized physical therapy services).

4. Aftercare and Transitional Programming

Many states require localities to have a nominal agency or other entity to support the public mental health system. However, few are as robust as Texas’ system of local mental health authorities, and those in our region were especially impressive to committee members with experience in other areas of the country. The counterparts in other states often serve chiefly a coordinating or regulatory role. The fact that our LMHAs are providers with a broad range of services and attract individuals with strong qualifications, is an enormous asset that can be leveraged for our state to be the leader in posthospital outcomes in behavioral health.

a. Discharge Planning

(i) Case Management and Benefit Coordination

Access to aftercare services and medications is improved when those discharged have their benefits obtained and confirmed. Of course, this involves personnel, but also access to information technology that at the very least expedites this effort rather than hampers it because of slowness and other inadequacies.

Orienting patients or caregivers to the potentially extensive array of benefit cards, documentation, access locations, scheduling processes, and so forth, is worthwhile as a prelude to discharge. However, the likelihood that such knowledge will generalize to behavior in a drastically different environment after discharge is slim if not reinforced and supported by individuals providing post-discharge support to patients.

Some local providers reported value in using SAMHSA’s SSI/SSDI Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR) portal (https://soarworks.prainc.com) for enrollment to those Federal programs and to locate resources, such as housing assistance, for their beneficiaries. If HHS does not have a comparable capability for service access, it might be a worthwhile system-wide investment because of the huge geographic dispersion and constant flux in providers makes it difficult for workers to rely on personal familiarity for every location.

(ii) Improving Coordination with External Agencies Preparatory to Discharge

We noted earlier that local providers perceive serious gaps in communication about pending discharges. Some pointed to the process used by the Waco Center for Youth as a successful model: “We received a letter that had a specific person for coordination and setting up for discharge. They attached a letter for the parents on how to communicate and the services they will provide. I think we need that at SASH. Parents are completely in the dark and are unable to drive to SASH to see the patient. There is no communication involving the parents.” Obviously, the issues underlying these perceptions need remediation.

(iii) Local Mental Health Authorities’ and CCBHC Certification May Facilitate Care Transitions

Texas’ LMHAs are charged with, among other things (41), facilitating the admission, continuity and discharge of patients in coordination with State Mental Health Facilities (SMHF), also known as State Hospitals. It is the responsibility of a LMHA to facilitate the continuity of services for the patient upon discharge from the SMHF. This includes coordination with community-based providers if the LMHA will not be the provider of services for the individual.

The LMHAs in Texas are pursuing certification as Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics (CCBHCs). The certification standards or program requirements for a CCBHC were developed by SAMHSA and are administered by Texas Health and Human Services (HHS). The CCBHC program requirements address: 1. Staffing; 2. Availability and accessibility of services; 3. Care coordination; 4. the scope of services; 5. Quality (CQI) and reporting; 6. Organizational authority, governance and accreditation. The program requirements which directly apply to the SASH redesign are availability and accessibility of services and care coordination.

b. Subacute and Transitional Residential Facilities

A resounding message from stakeholders across the catchment area was that a phased transitional step-down section of the hospital needs to be created. Many stakeholders noted that most people coming out of the extended stabilization services at SASH are not ready for a full immersion back into the community. Additionally, because of a lack of discharge and aftercare planning prior to discharged, most people are discharged without resources, such as transportation, housing, and community treatment, that is necessary for success in their recovery long-term.

One promising opportunity is to create supportive housing and other services at the SASH campus. Their goal would be transitional and a way-station to evaluate readiness and needs for suitable living arrangements closer to patients’ home communities. A study should determine if any of the current buildings can be repurposed for an array of needed services to help maintain patients functioning outside the hospital.

- We endorse the decision of HHS to seek a Request for Information to determine what community entities might be interested in providing mental health and/or social services at the SASH

- Housing options for patients who have severe mental illnesses, especially those with chronic, difficult to remit psychotic symptoms and need secure

Vermont has developed a number of homelike settings that are actually staffed and equipped more like inpatient psychiatric settings than the high-quality group homes they outwardly resemble. Patients discharged from the sole state hospital near Montpelier can locate to a setting close to their communities of origin. The settings house around 8 to 12 individuals. Patients on civil commitments have their order amended to remand to these settings, while allowing return to the secure hospital setting in the event of unsuitability or unauthorized departure. Vermont obtains daily-rate reimbursement for these services. We strongly recommend HHS investigate these options.

5. Timeliness and Continuity in Pharmacotherapy

a. Effective Transmission of Vital Current Treatment and Treatment History

The vital importance of an accurate and up-to-date treatment history lies in its potential to shorten time to symptom relief hospitalization itself. Problems with data exchange are not unique to San Antonio, but if HHS is looking for operational efficiencies, then optimizing treatment history data available to state hospital clinicians is a good opportunity. UT Austin’s School of Pharmacy is at the forefront of research on improving methods for tracking treatments across settings and could be a valuable partner.

b. Anticipating Potential Problems with Medication Maintenance

Improved coordination with aftercare services can factor in aspects of an individual’s medication regimen that may improve adherence. Relatively complex, multi-agent treatment requiring three or four administration times per day, for instance, are feasible in a hospital setting, but have sustainability challenges in less intensively supervised settings.

Access to monitoring and clinical lab specimen collection sites may also need pre-planning. For example, patients discharged from SASH following good response to clozapine (Clozaril®) require periodic blood monitoring with satisfactory results before pharmacies can renew a prescription, due to the risk that agranulocytosis can develop regardless of how long one has been taking it. Changes in FDA guidance has lessened the burden somewhat (weekly for initial six months, biweekly for months 7 to 12, and monthly thereafter). However, we learned that difficulties in obtaining labs lead to clozapine discontinuation with the risk of symptom resurgence. Missing three of more days of clozapine requires restarting titration and the CBC monitoring schedule, rather than resumption of the last dose. Abrupt reintroduction at even doses well tolerated previously is thought to increased risk of blood dyscrasias and the risk of seizures which is in fact greater than that of agranulocytosis (42).

It turns out that treatment discontinuities are perhaps even more prevalent for some of the medications, psychiatric and other medical, because of variation in the outpatient pharmacy benefits for which patient may qualify. HHS’s management of contracts with its managed Medicaid vendors may help is smoothing out the more frequent sources of disruption, but other beneficiaries and the health-care-unfunded patients further work may be warranted to evaluate the scope of the problem and possible solutions.

c. Ensure that Discharged Patients have a Medication Management Visit with a Prescriber Within Seven Days of Discharge

The current quality metric of an appointment with a mental health provider within a week of discharge does not necessarily require that it involve a medication prescriber. Doing that sooner rather than later contributes to treatment continuity and adherence and allows sufficient time to remedy kinks that may arise in dispensing (such as prior authorizations) with less disruption to therapy.

Other continuity-of-care recommendations for implementation on the outpatient side are described later.

6. Development of ECT and TMS Programs

Electroconvulsive therapy’s (ECT) well-established indications are for pharmacotherapy-resistant mood disorders and catatonia. It may be advantageous for antipsychotic-refractory schizophrenia without catatonic features although there is less data (43-45).

Of the 22 facilities registered in Texas with clinical ECT programs, only one, in Terrell, is within the state hospital system (46) ECT is available at two San Antonio hospitals, Laurel Ridge Treatment Center and Methodist Specialty and Transplant Hospital. SASH patients may be transferred to Terrell for ECT.

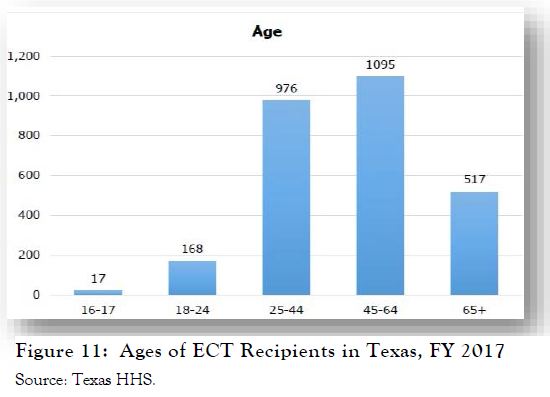

Statewide during FY 2017, 2,773 individuals received at least one ECT treatment. Their age distribution, shown in Figure 11, indicates that the most patients were in middle- to later-age adulthood (45-64 year-olds: 40%; 25-44 year-olds: 35%), while 18% would be classified as elderly/geriatric (46).

Statewide during FY 2017, 2,773 individuals received at least one ECT treatment. Their age distribution, shown in Figure 11, indicates that the most patients were in middle- to later-age adulthood (45-64 year-olds: 40%; 25-44 year-olds: 35%), while 18% would be classified as elderly/geriatric (46).

Insofar as those in state hospital care for extended periods have been, almost by definition, refractory to numerous pharmacotherapies and other interventions, improved access to ECT at SASH may be warranted. Public sector funding for this treatment has been in in recent years decline and this is unlikely to reflect improved efficacy of other interventions over this period. If ECT underutilization contributes both to patient hardship and prolonged state hospital bed occupancy, then establishment of an ECT service at SASH is warranted. Postdischarge outpatient maintenance treatment can be performed at other sites, or conceivably at SASH itself if it would improve accessibility to patients and contribute to sustainability of the service. We recommend the new facility include infrastructure to establish an ECT program.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a noninvasive, nonconvulsive treatment whereby an external magnetic field is applied to specific brain areas in a repeating, pulsatile fashion. It has FDA-approved indications for pharmacotherapy-resistant depression and has been studied in other psychiatric conditions that include schizophrenia, PTSD, and neurological conditions that include chronic pain and sequelae of stroke. Infrastructure requirements for rTMS, besides the equipment itself, are minimal, but should be incorporated into the new facility.

7. Install Modern Technologies for Communications, Patient & Visitor Use, and Service Integration

Stakeholders, both external and internal to SASH, lamented its antiquated and at times dysfunctional technology capabilities. New construction is anticipated to upgrade them, but we urge consideration of functions that, beyond the boilerplate capacities of telecommunications and internet access, would enhance quality of service, care, and visitor experience.

Specific recommended functions, discussed in other sections as well, include:

- Fulfill the objectives in earlier HHS reports to improve patient-care related information technology, including more modern and integrated electronic health records (17,18). Given patients’ extensive treatment, and at times judicial, histories, the capacity to scan select paper records should be incorporated to this system.

- Patient computer stations for training and personal use, appreciating the necessity of greater control over content and communications to ensure safety and appropriate use of state- owned equipment.

- A dedicated wi-fi network for visitors.

- Adoption of a wristband scanning or similar system to record patient activity attendance. Currently, patients have cards stamped for attendance as part of an incentive program in which they are redeemable for desirable activities or goods. Unsurprisingly, many patients lose these cards. Just as importantly, documentation of patient attendance at specific therapeutic activities is extremely useful for gauging progress, team summaries, and regulatory purposes.

- Some newer facilities use a silent alarm system in which a staff member needing assistance from others to help a patient’s behavioral stability can privately activate his or her own key-fob- type device that conveys information about his or her location. Those we spoke with in one adopting facility found enormous advantage because overt verbal calls for assistance are apt to agitate and inflame a patient further, and the electronic system communicates need beyond hearing distance.

- Videoconference capacities will be important to facilitate therapy sessions that involve distant family members, and the latter can participate alongside the LMHA clinician to foster continuity. This type of technology would remove transportation and communication barriers currently experienced by families and providers from rural communities. Installation of such equipment is not complicated in offices, and the main infrastructural factor will be quality of the internet broadband to handle the expected traffic. A method to arrange incoming calls needs to be established.

- On the other hand, spaces for “virtual visiting” for patients outside of staff offices does need special consideration with respect to equipment, balancing privacy with appropriate supervision and technical assistance, and access. We understand virtual visit stations have been installed at Rusk, and lessons from that experience will be useful in the SASH installation.

8. Family Participation in Treatment and Support

Specific building and landscape design recommendations to promote positive interactions with patients’ visitors are in the next section, so we address other programmatic factors here.

We strongly recommend that teleconference/telemedicine capabilities that link SASH therapist with their LMHA counterparts be used to maintain linkages and continuity. This offers an excellent way to involve families, especially for adolescent patients, given the difficulties families face in consistent visiting during therapist availability times.

Maintenance and enhancement of SASH’s current family overnight lodging capacities is also strongly encouraged.

We encourage development of a Family Resource Center within the new facility. Some informational materials such as booklet and DVDs can also be distributed in visiting areas to be situated nearer to patient units. The FRC we envision would involve peer support and benefit specialists who can aid families to obtain benefits for the patient or themselves, offer support and linkage to local advocacy, respite service, and other meaningful help that alleviates some of the burdens they experience.

Many hospitals encourage direct care nursing staff to provide guidance and support to families and acquaint them with practices used in the inpatient setting to help patients be consistent with self-care and activity involvement. The current skeletal pattern of staffing at SASH makes this difficult, but we highly encourage such communication nonetheless.

9. Issues Regarding On-Site Medical Care

Several key informants expressed interest in SASH developing the capability to treat non-life-threatening physical health conditions. This could enhance primacy care services on the SASH campus, reduce costs of transporting people from SASH to a primary care facility, and decrease potential disruption in care. In March 2018, STRAC distributed a Bexar County study conducted by Capital Healthcare Planning that analyzed data on homeless individuals and people with complex needs who routinely cycle between jails, emergency rooms, and inpatient care. The study’s findings suggested that people who frequently receive crisis services (e.g., emergency department visits and hospitalizations) have both mental health and physical health diagnoses. In fact, out of 18 categories of primary physical health diagnoses, from burns to cancer, at least 65% of the people in each category had co-morbid mental health problems, and across all 18 categories, 79% of the people had co-morbid behavioral health problems (47).

While our interviews revealed multiple positive outcomes of integrated care in the SASH catchment area, particularly at Tropical Texas Behavioral Health and Coastal Plains Community Center, the SASH capacity for integrated primary and mental health care services is limited. One medical director described his hopes that SASH would handle basic medical care, and that an integrated care infirmary on the SASH campus would help provide that care. It was pointed out that anyone who can receive medical care in the community while living at home should be able to have these medical conditions treated at SASH. Suggested examples of medical conditions that could be treated at SASH included pneumonia, hypoglycemia, cellulitis, urinary tract infections, and wound care. Further, this key informant described the need for an infirmary for the geriatric population, including closed rooms that could be quarantined to address contagious viruses, like influenza or norovirus, which is more likely to infect and harm geriatric patients. In a separate interview, LMHA and local hospital leadership staff indicated that SASH admissions can be problematic because no standard testing has been established for medical clearance, though medical criteria can sometimes prevent people from being admitted to SASH, even when their medical needs are not serious. For example, pregnant women cannot be admitted to SASH, even if there are no prenatal complications.

Another major concern of stakeholders was the growing rates of activity- limiting conditions among the seriously mentally ill population. The most prominent of these conditions are obesity and a variety of medical illnesses directly affecting mobility, including osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, neuropathies, and lower-extremity amputations resulting from complications of a patient’s chronic diabetes (48-50). The rising prevalence of these conditions among those with mental illness present challenges to psychiatric hospitals, which were seldom designed to accommodate people needing wheelchairs or walkers.

Other common medical comorbidities among individuals with chronic and severe psychiatric disorders include those requiring portable oxygen or gastrointestinal tube placement. In current medical practice, these needs are ordinarily met in the home setting rather than necessitating specialized personnel or major equipment. However, psychiatric hospitals have generally declined to admit patients with these needs.

When SASH had a census of over 3,000 in the 1950’s, it operated a three-story general hospital on-site. Combined with its then-remote location from other medical facilities, this patient volume made on-campus service delivery efficient. Currently, however, there seems little reason for SASH to duplicate the provision of complex medical services that are now available nearby. On the other hand, there are several high-frequency medical services that should be accommodated on-site both for expedient care and to alleviate the burden of off-campus medical consultations.

Both medical providers and community stakeholders offered recommendations:

- SASH should develop more standardized criteria of medical conditions that are exclusionary for admission to SASH and better coordinate with LMHA’s regarding these criteria.

- SASH should continue to provide general ambulatory medical care on site, along with dental services as well as on site EEG and EKG capacity. Medical exam rooms on each unit (or with very easy access) to allow physical examination and minor medical procedures without a client crossing the campus to a separate medical building is felt to be a paramount issue in design of the living units.

- HHS should perform study the issue of pregnant women who need admission to state hospitals. While this situation is not a common occurrence, fertility among patients with schizophrenia is rising (51) and making it prudent to anticipate a rising number of pregnant patients with serious mental illness the coming years. To not have SASH as an option for these situations may present a high risk for both mother and child.

- Take care in the design of living units at SASH that they are accessible to persons with physical limitations or in need of “in-home” medical procedures. Consider expanding the range of medical needs that can be served at SASH, given the limitations of staff number and training.

10. Special Programming and Aftercare Clinical Pathway for Individuals with Early Phase Psychosis

There is growing recognition that untreated psychosis is essentially neurotoxic, so that psychosis itself is frequently, though not universally, prone to worsen functional status. Early, aggressive intervention that supports and extends premorbid functioning as much as possible stands to reduce the burden of severe illness. Unfortunately, youth and early onset of illness currently militate against treatment adherence (52).

Consequently, there are numerous specialized clinical pathways and services tailored to the needs of young adults and adolescents experiencing early phase psychotic symptoms. Well-developed approaches have long been standard of care in parts of Australia, Canada, and some countries in western Europe (53). Interest and program development in this country has accelerated recently, spurred in part by a large effectiveness trial for first-episode psychosis (54).

An important observation is that the standard clinical settings that provide treatment for those with chronic and severe mental illness are frightening and alienating for those with recent onset of symptoms or those at high risk. Considering that the surroundings are often bleak and other patients show quite advanced debilities, young people are apt to reject the notion that they have much in common with these more chronically ill individuals, if indeed they acknowledge having an illness at all.

We therefore suggest consideration of distinct unit or subcluster within a unit for younger, early phase patients so that programming is better attuned to their needs and more likely to promote engagement with the self-care and other resources that can optimize the chance of a favorable outcome.

11. Educational Needs and Staff Development for Adolescent Patients

a. Focus on Adolescents with Demonstrable Need for Longer Stay Inpatient Care

There is a significant need to develop short-term inpatient services closer to adolescents’ homes and to phase out SASH’s use for this role.

b. Maintain and Enhance Full-Day School Program

A strong educational program with class settings that approximate as much as feasible what patients would encounter outside is vital, as discussed earlier. The new facility must have a school program capable of meeting the needs of patients of diverse ages and academic skills. It should not be so distant from the inpatient unit that an overly high threshold of behavioral calm is needed to attend. When school attendance is inadvisable on a given day, there should be a mechanism for educators to provide assignments for unit completion. The school program at SASH is provided through the school district of the hospital’s location, the San Antonio Independent School District. If the current agreement is to be altered so that it curtals staff and hours so that a school environment can’t be maintained, we urge HHS to establish a charter school or other entity to serve this essential need.

c. Recognize Skills and Augment Programming Needed in Care for Adolescent Patients

Direct care of adolescents in 24-hour settings requires specialized skills that differ from those developed in the course of working with adults who have severe mental illness (55). High staff turnover and the need to on-board and train new staff is deleterious to the management of these services, which demands consistency in the implementation of treatment plans, unit policies and tolerance for behavioral issues between staff members and over time. There are various means to promote consistency. Mentoring of new staff is vital to that process.

Clinical programming for adolescent patients needs to balance the need for constant structure with appropriate downtime. The involvement of rehabilitation staff is likely to be greater here than elsewhere.

12. Develop Alternatives to Hospitalization for Long- Stay Elderly Individuals

A number of elderly patients reside on the geriatric unit with no prospects for discharge. HHS should locate or devise care settings more appropriate for life-long placement than state psychiatric hospitals.

13. Caring for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Developmental Disorders

It is important for HHS and other agencies serving individuals with these disorders to develop plans for those who may need inpatient time-limited behavioral health care to address acute crises.

Nevertheless, we encourage that screening of patients’ suitability for state hospital admission focus on functional criteria that reflect their needs rather than diagnostic terms alone. Individuals now diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders experience a broad range of functional capacities. It is by no means a forgone conclusion that every person so diagnosed would not benefit from existing inpatient services nor that they would require intense support. The same is true of many people with IQs in the mild intellectual disability range, few of whom need more help with basic ADLs in a hospital setting than other behavioral health patients. One appealing feature of a hospital configuration with smaller units and subclusters within them is that if facilitates programming suited to the functional needs of individual patients.

For those individuals with chronic psychiatric symptoms or highly impairing and persistent behavioral disturbances, suitable post-discharge services are often problematic. However, stays in state hospitals are seldom appropriate, and community alternatives or specialized units within the state living center should be cultivated.

14. Eliminating Inpatient Suicides, Programmatic Solutions

Data from the 1990s and 2000s appeared to suggest that suicide is the first or second most frequent sentinel event in US hospitals, with an annual incidence of approximately 1,500 (56). However, an analysis published in November 2018 based on sentinel event reports to two databases show the incidence is far lower, ranging between 49 to 69 hospital-associated suicides per year (57). More recent data indicate growth in suicide-related behaviors most steeply among young adults (24,25), which may have ramifications for heightening suicide risk among inpatients with severe behavioral health disorders. Among adult inpatients, risk for suicide attempt and completion increases with psychosis, history of previous suicide attempts, bereavement, and feelings of hopelessness and self-deprecation (58-60). It had been suggested that one-third of suicides among behavioral health inpatients occur in the hospital. The remainder occur equally among patients who elope and who are on approved leaves; these estimates have been disputed, but it is certain that a number of inpatients elope with the intention of suicide by drowning, jumping from fatal heights, causing themselves to be struck by automobiles or inducing gunfire from others. Importantly, the months following discharge also incur high suicide risk.

It is important to keep people from committing suicide, but that is not quite the same as cultivating and supporting a desire to live. Psychiatric medications may remove some of the neural obstacles to the experience of positive mood (delusions, anhedonia, unsurmountable sadness), but they are generally not euphoriants – one become more susceptible to the satisfactions and pleasures that one’s life circumstances and interactions with the environment would normally provide, but they (for the most part, cf. ketamine) do not create them.

It is quite possible that improved environmental conditions that will accompany the new facility will help to create a more inviting milieu that encourages patients to engage positively. It is critical, nonetheless, that patient routines include gratifying activities and opportunities to make positive contributions that help one feel useful and appreciated.

Many if not most inpatient suicides occur among patients who are on a special observation status (61). Current best practices for patients on 1:1 for self-harm risk includes not just passive monitoring but engagement with patients and support in helping them be as close to meaningful social activities as possible. Training and supervision in doing so is strongly recommended.

Discharge planning should include at-risk patients making contact with those LMHAs with a designated role in triaging individuals with heightened vulnerability for self-harm. In several, this will be the team locally involved in HHS’s Zero Suicide Initiative and its Pathways Project which we encourage enhancing and broadening.

15. Substance Use and Addiction Treatments

The urgent need to address substance use disorders among patients with severe behavioral health disorders poses a major challenge to inpatient settings to implement treatments that will have durable impacts. Inpatient care obviously enforces a period of nonuse, which itself can be significant for those caught in a cycle of unremitting craving and use to alleviate it. Important elements of substance use treatment that can at least be introduced in the inpatient setting include psychoeducation about the hazards it poses to their illness and functioning, problem solving on alternative ways to get the gratification and relief that substance use offers, skills to resist triggers for use, and so forth.

Substance use and addiction are in large part dependent on context and environmental cues. Preparation for return to the same settings in which drug and alcohol misuse occurred is itself a risky proposition. This is especially true for individuals who may lack other activities to occupy their time. We therefore urge strong coordination with aftercare services to sustain the momentum toward desistance that the inpatient stay began.

16. Forensic Services: Reducing Reliance on SASH for IST Competency Restoration

The Texas Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services (JCAFS) focuses on gaps in system coordination and has made recommendations to improve access to mental health care for individuals in the criminal justice system. For instance, efforts to drop charges if an individual is admitted to a state hospital would help the state avoid costly criminal justice processes, and, if programs are effective in reducing recidivism, the state can save money on repeated incarceration. Initiatives like this, however, require beds to be readily available.

We strongly urge and support all agencies and judiciaries of state and local government to take a holistic view of the problem that overuse of state hospital resources for IST commitments are importing on the public mental health system.

When it is apparent that treatment is unlikely to ameliorate an individual’s psychiatric status so that they fulfill criteria for adjudicative competence, it is time for the justice system and defendants’ counsel to deal with that predicament and agree on suitable dispositions for the large majority of hospitalized defendants who would not meet criteria for civil commitment. Accordingly, we also suggest time frames in the recommendations section concerning statutory changes.

17. Forensic Services: Timeline and Structure for Incompetent-to-Stand-Trial Competency Restoration

Among those committed to inpatient settings to attain adjudicative competence, North American studies indicate that approximately 70% to 80% become fit to continue their legal proceedings. In practical terms, attainment of competence chiefly reflects response to pharmacotherapy for psychotic symptoms. Reductions in psychosis severity are significantly greater among those who attain competence than among those who don’t, with the latter group largely unchanged from initial assessment (34,62). In addition, competency non-attainers are older, have more neurocognitive or developmental impairment, and more extensive treatment histories.

As a practical matter, then, it does not take very long, especially with the benefit of a well-documented patient history, to establish whether an individual current lacking adjudicative competence will gain it in the near future.

We recommend that our state’s forensic experts in this area establish best-practice parameters to anchor expectations for treatment trial duration and to harmonize determinations of when one is unlikely to attain adjudicative competence. Addition of a standardized competency assessment tool may engender confidence in the judiciary that current competency and prognoses for attaining it can be reliably determined. The working group might consider the value of doing so across state hospitals.

18. Enhancing the Behavioral Health Workforce for SASH

Besides the obvious role of compensation, other factors can contribute to recruitment and retention. If done well, the new SASH facility is a potential asset to attract care providers.

We support HHS’s development of a campaign to publicize the benefits of working in a behavioral health state hospital setting. Among them is the opportunity to complete a treatment plan tailored to an individual’s needs. This may not sound all that innovative, but it is in fact a glaring contrast with the very short hospitalizations that predominate in other community settings where discharges occur at the moment a patient is minimally beyond the threshold needed for inpatient admission.

Engagement with training programs afford the opportunity to make a positive impression on future professionals. Attentiveness to mentoring and teaching that complements technical training are highly valued by students. It also bears pointing out that trainees who pass through on rotations are greatly affected by the general collegial atmosphere and morale in their appraisal of a worksite.

Facility Redesign II: The Built Environment. Developing a World- Class Facility for SASH

1. Contemporary Standards in Behavioral Health Facility Design

a. General Trends

Most behavioral health facilities built or refurbished in North America and Europe over approximately the past 15-20 years share aesthetic themes of openness, access to natural light, easy proximity to pleasing outdoor areas, patient privacy, variety in the density of social areas, acoustic comfort, and furnishings that strive to be homelike rather than institutional, yet also safe. The Facilities Guidelines Institute, American Institute of Architects, and other organizations provide guidelines that incorporate these elements.

“[F]rom the existing research…, there is a strong preference for the familiar, the humane and deinstitutionalized environments. Furthermore, studies have shown environments that prioritize the familiar to be economically and medically effective. However, … we are too often left with stark and institutional settings. Indeed, with regards to hospital design generally, Waller and Fine wrote: “We have now reached a position where far too many hospitals succeed in making people feel worse than they did when they came through the main entrance” (63)

At the same time, the persistence of patient suicides and other self- harming incidents has led to revised standards for physical precautions in patient areas, notably those that eliminate opportunities for intentional strangulation or hanging.

At the same time, the persistence of patient suicides and other self- harming incidents has led to revised standards for physical precautions in patient areas, notably those that eliminate opportunities for intentional strangulation or hanging.

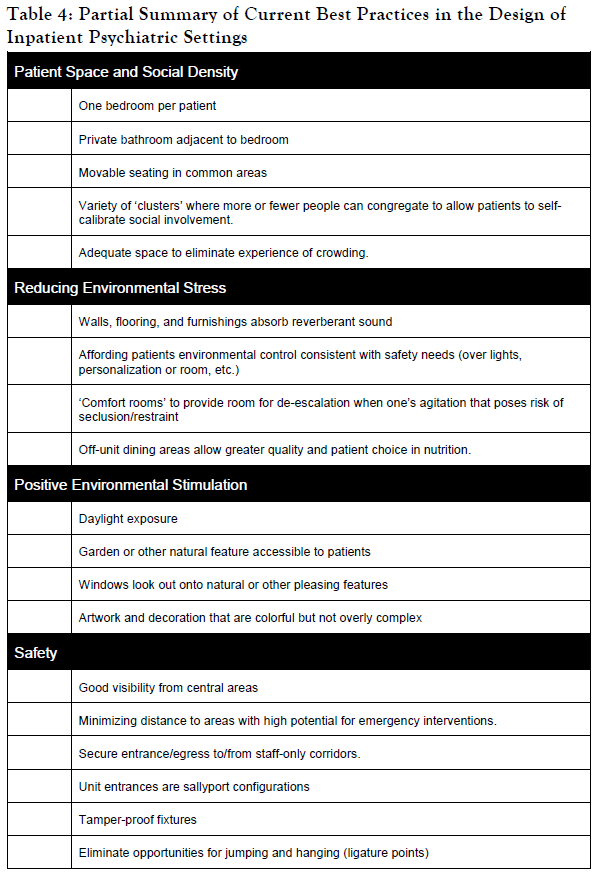

Table 4 contains a summary of design features currently adopted or strongly considered in recent projects. This summary is drawn chiefly from Ulrich and colleagues’ report (1) on reductions in aggressive incidents that accompanied a behavioral health facility design, but the same characteristics are recur in recent literature by others (2,3,63-66). Other facility features are drawn from Hunt and Sine’s (67) specifications for patient-centered design that are also cognizant of recent Joint Commission standards for safety.

b. Specific Standards

There are a number of recent behavioral health inpatient projects worldwide that endeavor to adopt or establish cutting-edge best practices. Some of these ideas are noted in the following sections on specific building elements. In general the standards set forth by the Facilities Guidelines Institute, Inc. (FGI) on psychiatric hospitals are an appropriate touchstone and realistic reference in fulfilling HHS’s request that we describe “best practices used in the design of the proposed facility”. Texas does not adopt or require FGI standards in its regulatory framework, but nearly all architects and designers are likely to, and they do embody what current literature in mental health emphasizes as appropriate for inpatient care.

It may warrant mention that the existing patient care areas at SASH only seldom comport with these guidelines, even earlier editions.

2. Unit Size

There is surprisingly little research on what is the optimal maximum patient census for self-contained behavioral health inpatient units serving various populations. Nevertheless, by modern standards, the current SASH layout of 40 adults and 20 adolescents is excessive. Some expert consensus reports place the maximum unit size for acutely ill adults at 15.(e.g., ref e.g., ref 69) However, staffing difficulties and fulfilling community demand in an era of dwindling bed capacity makes this seldom attainable in the U.S. A common desired maximum unit census is around 24 and 18 or fewer for adolescents.

The deleterious effect of mental hospitalisation, attributable in part to depersonalising, regimenting and sensorily deprived environments are widely known … [d]rab surroundings communicate to the patient ‘nothing matters’ which fosters the apathy being produced by other pressures. — Barton, 1976 (68)

As unit size grows, it is desirable to form groups of patients who follow the same schedule, have the same staff members associated with them, and participate in group activities together. These arrangements often correspond to treatment teams (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, etc.). Groups of this sort may be advantageous when a wide range of patient age and functional status complicates programming, so that smaller cohorts of similar individuals can be better served. Physical layout can also structure these smaller groupings into individual wings for further impart a more intimate and less intimidating social unit.

3. Design to Optimize Social Density and Patient Privacy

Built-environment researchers have distinguished spatial density, which is the area per person of enclosed space, from social density, which is the number of people in each space. Several studies have shown that social density is highly associated with crowding stress and patient aggressive behavior. Reduced spatial density, or room size per se, is less significant beyond a certain minimum area that avoids feelings of compression.

Achieving goals for comfortable social density often involves creating a range of distinct and sometimes differently sized social and seating arrangements. This enables patient to self-calibrate to the degree of social exposure they find manageable.

4. Design Admission and Facility Entryways to Convey Therapeutic Atmosphere

Building features upon entry must be calming and welcoming.

5. Create Unit Entry and Reception Areas that are Inviting and Secure

Patient areas in modern medical/surgical facilities have relatively open-access floor plans, in which nursing stations or other staffed areas do not serve as barriers for visitors and patient movement. Psychiatric settings, in contrast, usually have locked doors, but often retain the placement of a reception or other well-staffed area some distance from the unit entry. In some experts’ view, this is inadvisable because it creates an unwelcoming entry and disorienting to visitors. While cameras and remote entry buttons are ubiquitous in these situations, eyes-on surveillance of those passing through the door becomes inconsistent. Placement of nursing station and other points of observation are among the most significant design elements in behavioral health settings, and its prominence to entering visitors is another important consideration (2,66,67).

There is some evidence that small-group circular arrangements of furniture may promote socialization. Exclusively linear arrangements, in any event, create a “bus depot” environment that is alienating and unattractive.

6. Access to Fresh Air and Outdoor Spaces

Facilities in urban areas with predominantly vertical construction contend with the challenges of providing open space and natural light for patients. The SASH site, fortunately, has an abundance of open space, with a pleasing landscape and topography to meet these needs.

Patients and staff have a distinct preference to avoid overly-enclosed outdoor space because they feel confining, lack desirable natural views, and are not found conductive to walking. A fully-enclosed courtyard-type arrangement is therefore disadvantageous. Moreover, in our climate enclosed outdoor space threatens to reduce air flow in high heat, complicates drainage, and can hamper the efficient maintenance and watering of plantings.

Landscaping and hardscaping should be suitable for strolling, and at least a portion should provide safe surfaces and grading for walkers, wheelchairs, etc. Nature trail-type, curved walking paths and other outdoor activity areas are inviting for outdoor recreation.

Shaded areas and outdoor drinking water facilities will be necessary.

7. Patient Rooms and Bathrooms

Current guidelines call for a minimum of 100 square feet of net usable/clear floor space for a single room, and 80 sq. ft per person in multi-patient rooms. Two patients per room is now the accepted maximum.

Single-patient rooms are preferred in most settings to minimize conflict, allow enough personal space, individualization of light at nighttime, and allow a personal calming space when needed. The use of built-in rather than movable furnishings (bed platforms, desks, storage, etc.) can offer an appealing design element and reduces risks of damage or injuries from such items being misused or weaponized. There are guidelines, though, for the accommodation of persons of size and satisfying these requirements with built-ins is to be determined.

Some rooms may be sized as doubles to provide additional flexibility and fulfill requirement for handicapped accessibility or other bedding for medical and personal size needs, and so on when needed. They would also provide patients on 1:1 constant observation with adequate space for the staff member to stay with patient comfortably. We urge that rooms designed as legal doubles to provide this flexibility not be routinely used to increase patient census.

Adjoining bathrooms comprising at least a toilet and sink are now standard practice. Guidelines specify preference for direct entry from the bedroom, though some facilities also install doors from the main corridor.

Shower and bathing facilities not within the adjoining bathroom may serve several bedrooms, though a minimum of one shower/bathing area for every six beds is specified (37).

8. Create Open Settings that Encourage Interaction

In general, unit design should strive to reduce the “fortress”-like intersection of patient and staff areas.

Nursing stations can combine an open-counter space behind which is a glass- enclosed room for privacy and safe completion of tasks.

The exact configuration and degree of openness is a matter of debate with no single solution. We can report our discussions with nursing leadership in a new facility that replaced older inpatient units that incorporate a more open nursing station than staff were accustomed. When the design was presented, there were widespread threats to resign rather than move into the new building. A year after their move-in, however, staff are extremely satisfied, patient aggression has declined, and there is a sense of disbelief that they tolerated the former layout so long.

9. Maximize Exposure to Natural Lighting and Use Appropriate Artificial Light Sources

Besides the visual appeal of the sky and sunlight, diurnal variation in natural light exposure regulates many physiological functions in a circadian fashion. Individuals with mood disorders are exquisitely sensitive to dysregulation of one of them, the sleep/wake cycle, that is largely governed by patterns of exposure to natural light. Chronic exposure to artificial light that disassociates one from the prevailing regional rhythm of sunlight worsens mood disorders. Both mania and depression can be exacerbated when one’s sleep/wake patterns desynchronize from the natural environment.

Unremitting exposure to interior overhead fluorescent lighting is suspected to be especially problematic. Current design practices favor LED lighting, which offer a wider choice of light spectra appropriate for each installation area. They are also more reliably controlled by dimming mechanisms.

10. Use Layouts and Materials that Prevent Unfavorable Acoustics

Chronic exposure to highly reverberant spaces is noxious in general, and there are certain patient groups for whom this form of stimulation is especially aversive. Patients, notably those with IDD, are discomforted by high stimulation of this sort. It is also believed that psychotic patients, for whom auditory hallucinations are the most common perceptual disturbances, a high noise environment is deleterious. Long, echoic corridors are also discouraged by built-environment experts for psychiatric patients. They also amplify the sounds of patients in distress, making it difficult to redirect other patients and avoid contagion of upsets. Flooring material plays a significant role in managing ambient sound. Newer sound-absorbing products have high durability resilience to dirt and liquid penetration.

11. Create Adequate Spaces for Treatment on or Close to Units

a. Consulting Room and Activity Space

One of the greatest concerns by SASH staff was the limited on-unit space for seeing patient and running group activities.

We recommend a minimum of two rooms per inpatient unit for seeing patients individually or with family. Adequate distinct spaces for group activities should be available both on the units and nearby. A separate meeting room for staff on the unit helps to maximize the participation of direct-care staff.

Adequate space for therapeutic activities on or near patient units should enable a mixture of activities or groups to occur simultaneously. Enough storage for equipment used in these activities should be anticipated.

b. Staff Office Locations

It may be desirable for some team members to have their offices on the unit itself. This has the advantage of promoting team integration, efficient access for seeing patients, and more opportunities to observe and evaluate functioning. On the other hand, off-unit office space is more conducive to meeting with individuals from outside without need to bring onto unit and can be more efficient for those caring for patients on more than one unit.

c. Medication Administration

We assume that a modern pharmacy system (such as Pyxis, Omnicell, etc.) will be part of the new facility. Many behavioral settings have also adopted mobile carts that integrate with this system to enable dispensing where patients are. When it works well, it is perceived as less disruptive to patients’ day and enables a higher quality of interaction around this important part of one’s therapeutic routine. From a design standpoint, we heard from facilities occupying newly completed projects found some door widths can be problematically narrow for some equipment. Earlier experience at SASH with a similar mobile point-of-service system was not favorable. It is not hard to imagine some patients becoming intrusive and fiddling with the devices since they are, at least initially, among the more novel things they encounter. Nonetheless, old-style wickets and passthrough windows are more institutional and restrict interaction at an important moment of personalized attention. We recommend reconsideration with the design team toward implementing a system that is conducive to interaction, teaching, and avoids associating medication with an impersonal or imposed experience.

d. Spaces to Promote Patient Calm and Regain Composure

Guidelines recommend a ‘comfort room’ that is a calm space for patients to regain composure and defuse escalating behavioral situations. Ideally, it averts the need for seclusion orders in a number of instances.

e. Medical Examination Room

Each unit should have a medical examination and treatment room with at least basic capacities for physical examinations, phlebotomy, treatment of minor injuries, first aid, and computer access to electronic medical record and ordering portals. Other equipment may be desirable for which practitioner input would be useful (e.g., glucometers). Net usable space should be adequate to allow other staff to be present for procedures, as indicated.

Defibrillator equipment needs to be available at locations that state requirements or those of other accrediting bodies specify.

12. Staff Support

There must be adequate off-unit space for staff breaks, rest, and dining. Given short break times, these must be close to their work sites, and incorporate comfortable outdoor areas.

Facilities for training and conferences are important for staff development. Some can be within the building secure perimeter, while others can be elsewhere in the building or in new or rehabilitated structures on campus to permit outside attendees.

Washroom facilities for staff should be easily accessible from the inpatient units and numerous enough to accommodate the maximum expected workforce at a given time.

There are guidelines for the number of parking spaces that consider the number of employees. Providing secure escort to one’s vehicle at night should be included in design of the employee exits.

13. Accessible, Centralized Off-Unit Facilities and Amenities

The facility will have a variety of centralized patient services and amenities. Their location should be convenient and safe enough to enable for as many patients as possible to go them unescorted if they are capable. These will include on-site hair salon/cosmetologist, dental care facility, patient store, worship areas, library, gymnasium and fitness center, independent living rehabilitation areas, and so on.

Policies and physical infrastructure should support appropriate patient access to telephones and computers.

14. Family Space for Visiting

We urge that comfortable, homelike surroundings for visitors be created adjacent to inpatient units. One such area could serve up to two units.

For patients who can leave the unit accompanied by visitors, amenities like dining areas, activity areas that also include child-friendly elements, handicap accessible walking trails, and attractive shaded outdoor garden-like areas need to be incorporated.

Units should include ‘virtual visiting’ via audiovisual and computer facilities. Methods to arrange and accept incoming calls need to be developed as well.

15. Safety

The Joint Commission (TJC) promulgated new environmental standards for patient safety that aim to eliminate physical elements that patients could use to aid in suicide. Hanging was the cause of death in about 75% of cases reported to TJC, and elimination of ligature points is prominent in design efforts to mitigate suicide risk. Toxic chemicals used for cleaning or other purposes have been intentionally ingested to cause death, and special attention and training concerning their use and storage, as well a preference for nonlethal products, need to be considered.

The most common locations for suicide on inpatient units are bathrooms, bedrooms, and closets. Bathroom design now has an extensive number of features and regulatory requirements intended to mitigate suicide. These are detailed in, among other sources, the 2018 Behavioral Health Design Guide (67), which is cognizant of recent TJC and other regulatory changes in recent years. There are vendors who provide pre-constructed bathroom modules that fulfill these requirements that may potentially reduce onsite construction times and perhaps costs, dependent on shipping and aspects of the building during construction that make it amenable to their installation.

There are now a multitude of guidelines and regulatory standards for patient and staff safety on behavioral health inpatient setting, which are well known to HHS and any qualified designers for a new facility, so they do not need to be reviewed in detail here. Elimination of ligature and hazardous jumping points are emphasized in current design. Outward opening doors prevent patient barricade, but if the open door is too prominent in the corridor it may conflict with other safety guidelines; recessing the entry into an alcove sometimes solves the issue but can compromise visibility that may require installation or mirrors. Sometime a wicket-type arrangement in which an outward opening smaller door is built into the main inward- opening door, but if not large enough barricading and inefficient access still can result. In any event, all these specialized features contribute to cost. These elements should not come at the expense of other clinically important resources.

Furnishings and fixtures that are pleasant, movable and noninstitutional but that also are resist weaponization are a challenge. There are vendors currently who do produce seating and other items that are appealing yet weighted to prevent throwing and made of relatively durable materials. Fabric and other coverings have a limited useful life in these setting, but this should not deter their use when they can contribute to aesthetics and comfort. The more soil resistant and removable for laundering the better, but like any living facility periodic replacement has to be anticipated and budgeted.

One major factor not tethered to building infrastructure, though, is staffing pattern. Except for the Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit, the staff-patient ratio is low for a highly impaired patient group. The move to redesigned smaller units with single rooms is expected to reduce the safety risks from aggressive or agitated behavior. Nevertheless, lean staffing leaves little leeway if a behavioral emergency develops that requires many staff members exclusive attention, even if those from other units come to assist. One or two patients requiring monitoring while they are in in seclusion/restraints or in need of 1:1 observation can easily detract from the ability to meet the needs of other patients. When these developments result in delaying or unfavorable scheduling for the already-brief break for a 12-hour shift, one can anticipate adverse impact on morale. Solving this issue goes hand in hand with workforce considerations, but a persistent bias toward lean staffing can be risky.

We noted earlier the adoption in some new facilities of silent call alarms that staff keep on their person. We recommend that HHS and designers evaluate this technology for its potential to more rapidly dispatch staff where needed in an urgent situation, and the likelihood that it is less inflammatory to the situation than verbal shouting for assistance.

Clear and consistent signage about escape routes and other directions can be lifesaving in emergencies. The Whole Building Design Group refers to the Department of Veterans Affairs guidelines as a worthwhile example (https://www.wbdg.org/ffc/va/vadeguid/signage.pdf).

16. Educational Facilities for Patients

We discussed earlier that it is highly desirable for adolescents to receive instruction in an environment that best approximates a community school program. For adolescents that will mean changing classrooms between teachers with some degree of specialization. On smaller inpatient services without an associated day program, this often means a teacher for language arts and perhaps social studies and another for chiefly math and science. Rehabilitation staff often organize art and music and physical education. Many students will have individual education plans that require speech/language, OT, PT, and other services provided in the course of the school day. Designing the school should take careful account of the configuration of the planned educational program and meeting the needs of students receiving these additional support services.

Adult patients may be working toward their GED certification. Support for continuation of these efforts during extended hospital stays is strongly encouraged. Study space and tutoring areas, access to online material and ability to print all pose logistical issues that facility design should recognize.

17. Training, Continuing Education and Career Development

Some stakeholders expressed strong interest in SASH serving as a regional resource for training career development in the behavioral health fields, “so providers in the rural community can come to SASH and learn how to treat patients and take it back to their communities.”

18. Resource Mall

In a transitional living environment, the transitional team and providers from the client’s community of origin would work collaboratively to identify resource needs and complete aftercare and discharge planning. Stakeholders suggested a “resource mall” as part of a campus redesign to house benefits counseling, assist with obtaining identification cards, housing application, transportation planning, and related services to support people in their recovery as they transition to the community.

19. Plan Medical Capabilities and Flexible-Use during Crises or Disasters

We recommend building certain contingency plans into the design. Areas for consideration include:

Isolation areas in case of highly transmissible infectious diseases reaching outbreak proportions. Ventilation systems that enable one or more to become negative pressure rooms was also suggested. Or course, this is also useful for patients suspected of possible tuberculosis until active disease can be ruled out or antimicrobial treatment weakens its transmissibility.