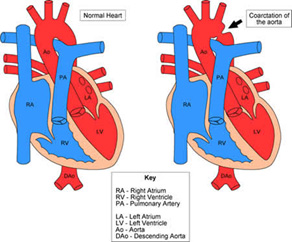

Coarctation of the Aorta

Coarctation of the aorta is a narrowing that usually occurs near the site of insertion of the ductus arteriosus. It frequently occurs in association with other heart defects, including bicuspid aortic valve in 50% of patients and VSD in 30-60%.

Coarctation of the aorta is a narrowing that usually occurs near the site of insertion of the ductus arteriosus. It frequently occurs in association with other heart defects, including bicuspid aortic valve in 50% of patients and VSD in 30-60%.

Nearly half of patients develop symptoms within the first month of life, often in conjunction with closure of the PDA. They present with systemic hypoperfusion, metabolic acidosis, and congestive heart failure. They have prominent upper extremity pulses and weak lower extremity pulses. Patients with less severe coarctation or sufficient collateral development may present as late as adolescence, usually with a murmur or hypertension, exercise intolerance, headaches, or angina. The murmur is systolic ejection and best heard over the left interscapular region. A CXR may show rib notching from hypertrophic intercostal arteries. Diagnosis is confirmed by echocardiography, which will also show associated defects. A peak gradient of > 20 mmHg by echo suggests significant coarctation.

Neonates presenting with profound acidosis should be treated similarly to interrupted aortic arch (see below section on IAA) to be stabilized medically prior to operative intervention. Surgical repair is via left thoracotomy (right thoracotomy for a rightward aortic arch). For neonates, primary treatment is extended end-to-end anastomosis, whereas adolescents and adults usually require patch angioplasty or interposition graft due to limited aortic mobility. Another technique is subclavian artery flap angioplasty, where the left subclavian artery is divided and the proximal portion is turned down onto the aorta for reconstruction. This, however, may affect limb development. Re-coarctation occurs in about 10-30% of patients following repair as an infant. Balloon angioplasty has a 90% success rate when employed for re-coarctation, with a 50% re-intervention rate at 20 years.